Amid the smoldering embers of the Civil War, the states are anything but united in Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales. It’s a bitterly divided nation where the local ferryboat captain explains that in order to do business, “you have to be able to sing ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ and ‘Dixie’ with equal enthusiasm.” Through this landscape rides the title character, once a mild-mannered Missouri farmer before his family was massacred by renegade Union marauders. Seeking vengeance, he rode for a while with some unreconstructed Confederate bushwhackers, the band of them betrayed by their leader (John Vernon, of course) after surrendering, gunned down in cold blood while pledging allegiance to the U.S. government. Josey Wales only escaped with his life because he refused to take part in the sham ceremony, because Clint Eastwood characters pledge allegiance to nobody.

The surly, monosyllabic Wales just wants to be left alone. But what’s so winning about this expansive, enormously entertaining picture –arguably the first great film directed by Eastwood– is that our archetypal loner can’t help but keep collecting strays on his picaresque journey across an America in the process of putting itself back together. Whether it’s the fresh-faced young rebel who idolizes him (Sam Bottoms) or a wry Cherokee elder in an Abraham Lincoln outfit (the screamingly funny Chief Dan George) and a Navajo gal who doesn’t speak a word of English (Geraldine Keams), Wales is constantly stymied in his attempts to ride lonesome. Soon he’s also stuck protecting a prim and proper Kansas pilgrim (Paula Trueman) and her spacey granddaughter (Sondra Locke) along with a mangy, old mutt who won’t run away no matter how often Josey spits tobacco juice on his head. The ever-expanding supporting cast keeps annoying and infecting our sullen, single-minded protagonist with their warmth and humanity. The Outlaw Josey Wales has got all the plot mechanics of a glowering Eastwood revenge Western but –like its hero– the movie keeps getting dragged off somewhere gentler and more compassionate.

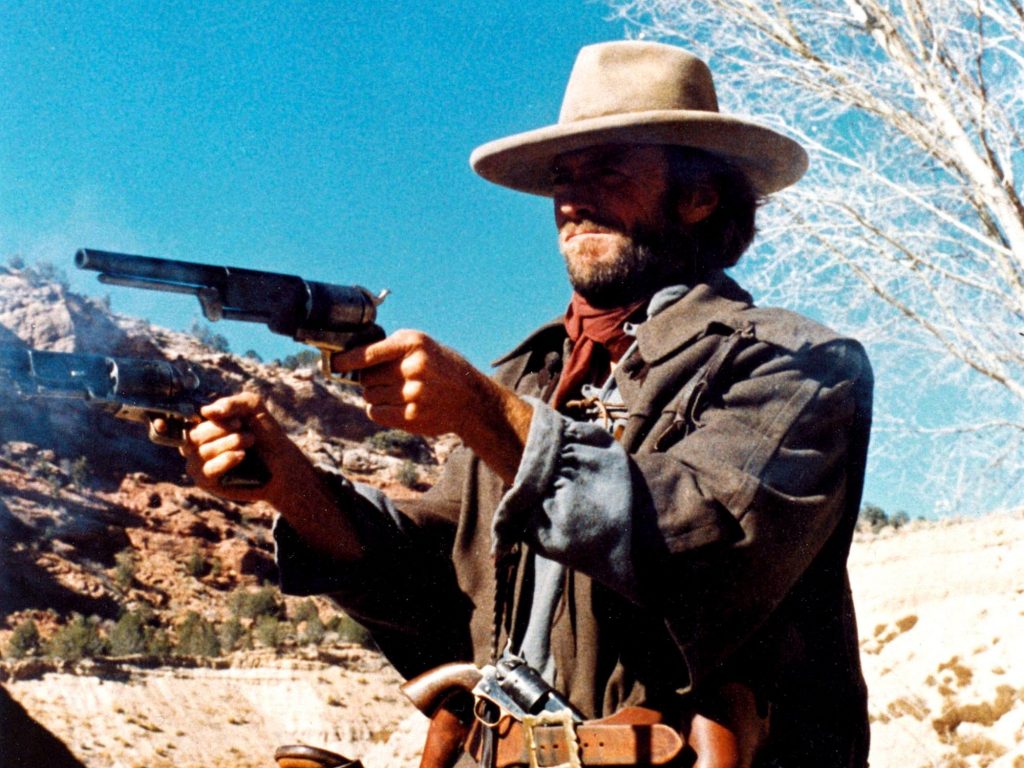

That isn’t to say the film doesn’t also deliver the kind of awesome bloodletting audiences expected from Eastwood at the time. Wales is one of his most mythic creations, a gunfighter of superhuman prowess whose reputation precedes him from town to town. (He’s one of those characters everybody spends all their time talking about in hushed, reverent tones whenever he’s offscreen.) It helps that Clint has never looked cooler. He’s typically either backlit in silhouette or filmed in harsh side-light through windows casting his features in shadow, a badass scar from a saber wound bisecting the scraggly beard on his left cheek. Pursued by half the U.S. army and every two-bit bounty hunter in the American South, the scuffles and shootouts offer a cornucopia of classic Clint one-liners, like “You gonna pull those pistols or whistle ‘Dixie’?” and the immortal “Dyin’ ain’t much of a living, boy.”

But it’s worth noting that the movie’s two most anticipated confrontations end not in violence but rapprochement, defused by wounded, exhausted pragmatists who are sick of all this mayhem and war. Great Westerns are never about the eras in which they’re set but rather reflect the times in which they’re made, and Josey Wales is pointedly a post-Vietnam picture made in the disillusioned wake of Watergate, released during America’s bicentennial summer. It’s got all Eastwood’s usual suspicions of government and contempt for institutionalized power, as fugitive Wales kids around with the Cherokee Chief saying, “I guess neither of us can trust the white man.” When this wagon train of misfits finally finds a home at a Texas farm, the movie briefly becomes a utopian vision of outcasts in harmony, as if to prove Josey’s earlier pledge to Will Sampson’s Comanche warlord: “Governments don’t live together, people live together… And I’m saying men can live together without butchering one another.”

The Outlaw Josey Wales was based on the novel Gone to Texas by the purportedly Cherokee author Forrest Carter, who rather embarrassingly for the production was revealed after the premiere to be former Ku Klux Klansman Asa Earl Carter, who penned George Wallace’s “Segregation Forever” speech before changing his name and writing both this book and The Education of Little Tree. (The dude is a whole other article unto himself.) The screenplay was by Sonia Chernus and the great Phillip Kaufman, the latter originally hired to direct. But Kaufman – who went on to a brilliant career helming contemporary classics like The Wanderers, The Right Stuff and The Unbearable Lightness of Being – wasn’t shooting economically enough for his notoriously thrifty and impatient producer/star, so Eastwood fired him and took the reins himself. (After this incident, the Director’s Guild of America established what’s colloquially called “The Clint Eastwood Rule,” barring a movie’s star from taking over after firing the director. This explains all the stories about Mel Gibson’s hairdresser calling “action” and “cut” on the set of Payback, and why people are still arguing over who actually directed Tombstone.)

There’s no trace of this behind-the-scenes drama in the finished film, which is quintessentially Clint in its prickly libertarian bent, egalitarian embrace of outsiders, and crowd-pleasing, barnyard humor. (He sure loves that tobacco spit.) It also represents a huge leap for the filmmaker, not just in the picture’s scale but thematic complexity. In 1973 Eastwood directed both the viciously sadistic, supernatural revenge Western High Plains Drifter and the delicate, May-December romance Breezy, in which gruff, fifty-something square William Holden quite touchingly falls for a free-spirited hippie chick a fraction of his age. The Outlaw Josey Wales is the first of Eastwood’s directorial efforts to try and reconcile these two seemingly contradictory sides of its director’s personality: the snarling, reactionary avenger and the groovy, NorCal dude who digs foreign films and jazz. (It’s a tension that animates all his most interesting work, and to this day remains unresolved.) Heck, the relationship between Josey and Sondra Locke’s young space cadet – admittedly the most forced part of the film – is like if Dirty Harry started dating Breezy.

In a lot of ways Wales is an inverted Unforgiven, which is about a farmer getting in back in touch with his old murderous, antisocial, evil self; here we’ve got a cold-blooded killer reconnecting with others and finding his way back into a community. Josey is a much more hopeful movie, made by a younger, more optimistic man. (Clint was 46 at the time, kicking off what would become a career-long habit of playing parts for which he was 20 years too old.) It’s also quietly radical in its treatment of Native American characters, matter-of-factly including a lot of ugly historical truths Kevin Costner would get far too much credit for “confronting” 14 years later in Dances With Wolves, while also seeing these people not as stoic symbols of suffering but rather as funny, idiosyncratic individuals. Chief Dan George has such a playful rapport with Eastwood you’ll wish they’d made a few more pictures together. He also delivers, for my money, the movie’s best line: “I never surrendered. But they got my horse, and made him surrender.”

Eastwood has been such a critical darling for so long now it’s difficult to remember how despised he once was among the intelligentsia, considered a wooden actor who made vulgar, fascist bloodbaths and redneck country music comedies with an orangutan. The French were onto him way before us, and in 1985 when Eastwood was made a Chevalier des Arts et Lettres by France’s Ministry of Culture, The New York Times Magazine ran an astonishingly mean-spirited, 6,400-word hit-piece mocking “The Clint Eastwood Magical Respectability and European Accolade and Adulation Tour.” But he did have an unexpected early ally in Orson Welles, who during a 1982 appearance on The Merv Griffin Show took a moment to champion Eastwood as a filmmaker, and The Outlaw Josey Wales in particular. Given their respective standings in the culture at the time, this today would be like seeing Martin Scorsese talking about how much he admires the work of Rob Schneider.

As recounted in Richard Schickel’s often alarmingly obsequious 1996 Clint Eastwood: A Biography, Welles said, “An actor like Eastwood is such a pure type of mythic hero-star in that Wayne tradition that no one is going to take him seriously as a director. But someone ought to say it. And when I saw that picture for the fourth time I realized it belongs with the great Westerns. You know, the great Westerns of Ford and Hawks and people like that. And I take my hat off to him.”

“The Outlaw Josey Wales” is currently streaming on Netflix.