There may be no force more powerful or insidious in Britain than the class system. Despite the progress the country has made over the decades, it’s a land still perniciously dominated by the colonial attitude that declares your status in birth and death to be rooted in who you were born to. The entertainment industry on this side of the pond remains dishearteningly defined by this, with many talented working-class creators stuck beneath the class ceiling while larger arts funders flit between kitchen sink miserabilism or cravat-heavy period dramas to represent the nation on screens big and small. Forgive my bluntness, but sometimes, you just need a good old-fashioned Fuck the Rich film to cleanse the palate. Perhaps inevitably, one of the greatest examples of this in British cinema had to come via an American.

Blacklisted by Hollywood in the 1950s, American director Joseph Losey made the leap across the pond and spent the last half of his long career making works in Britain. Often, said films were so inimitably British that it was hard to imagine a Yank behind the camera. 1971’s The Go-Between, for which he won the Palme d’Or, is an aching and unexpectedly perverse examination of the upper-lower class divide that mines the forbidden romance between a farmer and a genteel lady for tragedy. Released eight years prior, The Servant, adapted for the screen by playwright Harold Pinter, is a far more caustic dissection of the same divide. Why bother uniting with the privileged side when you can completely consume them?

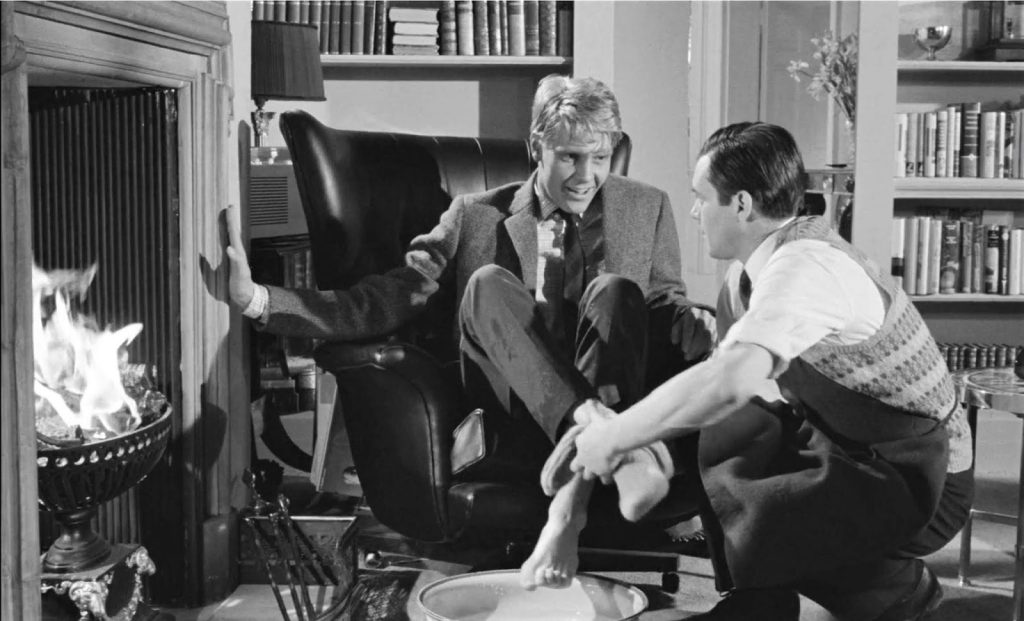

James Fox (the patriarch of a prominent and controversial British acting dynasty) plays Tony, a happy-go-lucky rich boy who doesn’t seem to do much but has cash a-plenty in his pockets. As is the right thing to do for gentlemen like him, he hires a manservant. Hugo Barrett (Dirk Bogarde) is seemingly perfect: hard-working, dutiful, and docile. Tony’s girlfriend Susan is suspicious of him, and rightly so. Barrett is scheming with his lover Vera, who he passes off as his sister to gain her employment in Tony’s home, to all but devour his employer. Soon enough, Tony is a drunken waste of space, utterly dependent on the manservant who has flipped the dynamic to become the master.

It’s remarkable how little pity The Servant has for Tony. He’s not especially evil, especially compared to the great snobs of British entertainment, but he is clearly cloistered by his money and status to the point of total uselessness. It is, however, a little strange that he would choose to have a manservant in the early ‘60s, as Swinging London and the muddling of the class divide is about to kick off. Perhaps therein lies his biggest error, a total misreading of the times. For Losey and Pinter, to be blissfully unaware of your privilege is no justification, and it doesn’t protect you from punishment. There’s no Saltburn-esque “but maybe the rich people are OK” cop-out. Here, the working-class schemer gets to reign supreme, a brief moment where centuries’ worth of destruction is evened out, however callously.

If class is about power, so is sex. While both Tony and Barrett are ostensibly straight, there’s a heavy streak of the homoerotic throughout The Servant that is closer to text than subtext. Their mutual desire seems as evident as their growing distaste for one another, a dynamic that only becomes more bitter and devoid of tenderness as their roles are switched. They are constantly looking at one another, often surreptitiously, peering to see who is in charge of which space and at which moment in time. In one scene, Tony and Susan return home early to discover Barrett and his “sister” cavorting in his bedroom. Tony stands at the bottom of the stairs, looking up. He doesn’t see Barrett himself but his silhouette, and he’s clearly naked. Stuck at the bottom, shrouded in shadows, it’s obvious that Tony is no longer in control. For Barrett, he is often found gazing at his employer through the proxy of a mirror, the true intentions clear on his expression where Tony can’t properly see. It reveals the lack of servile instinct in Barrett, a man who plays the role of the lesser but is never such.

If The Servant had been made earlier – perhaps during the Second World War, when stiff upper lips and noble gentlemen were more cinematically heroic – it’s unlikely Barrett would have been allowed to win. His agenda would have been seen as too cruel. For Losey and Pinter, however, the cruelty is the point. The whole damn system is cruel. There are countless Tonys throughout the centuries who have done to the Barretts of Britain what has happened to him in his own home. And the lowly Barretts are expected to shut up and accept it, to see it as their rightful duty. But it was 1963. It was time to settle a few scores, to screw up the system and start over. Or, at the very least, wreck a few spoiled brats’ lives.

“The Servant” is available on Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection.