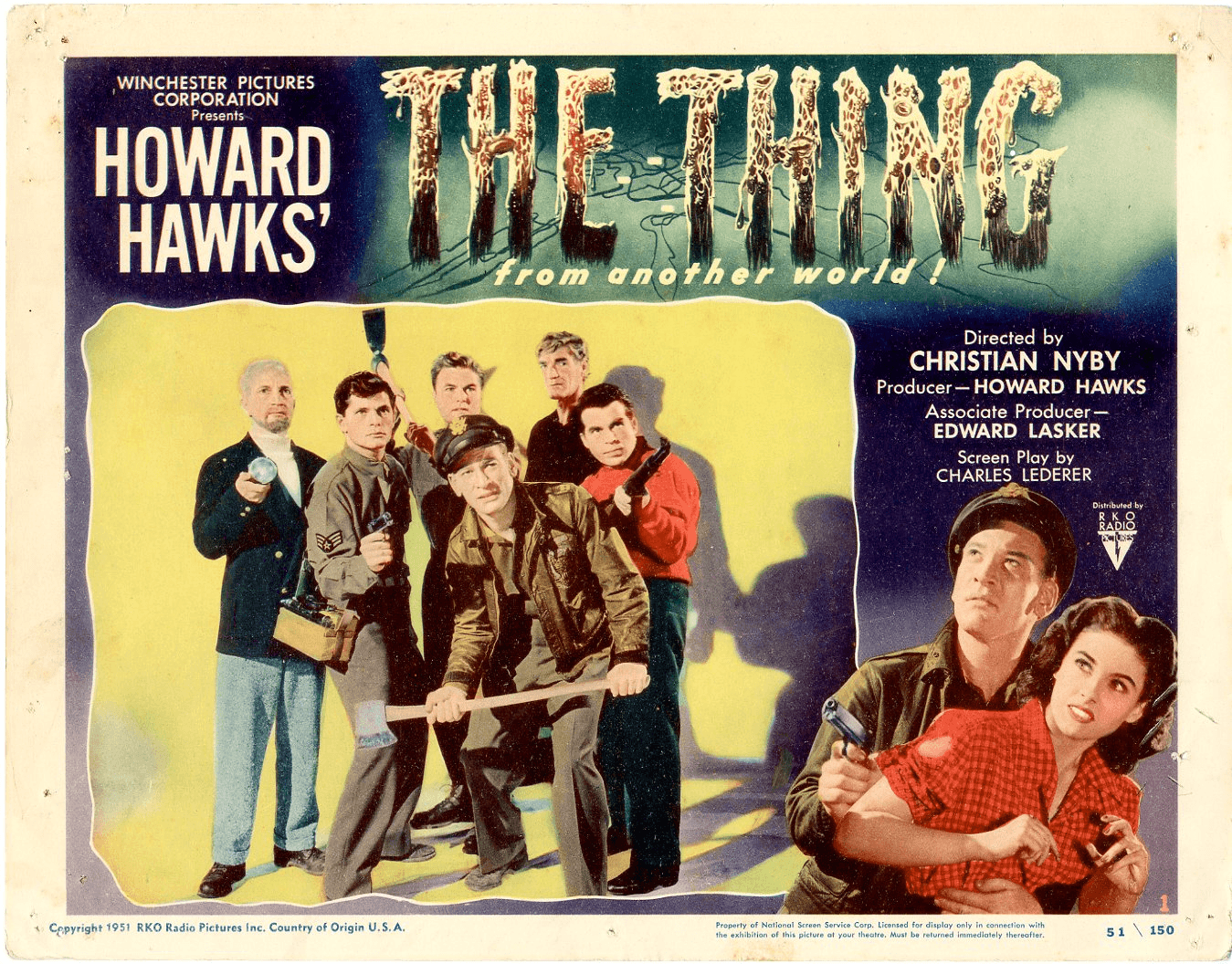

“An intellectual carrot,” exclaims bewildered journalist Ned “Scotty” Scott (Douglas Spencer), “the mind boggles!” This line comes about halfway through the sci-fi horror classic The Thing from Another World, after it’s been explained to Scotty and the other occupants of a North Pole research outpost that the extraterrestrial entity that they’ve excavated from the ice, and that now threatens to destroy them, is essentially a bloodsucking, advanced form of vegetable. It’s hardly a mental image that inspires much fear or dread, especially to a modern audience—and the actual appearance of the creature, played by the towering James Arness, certainly doesn’t help. Today, it’s exceedingly difficult for a man lumbering around in a monster costume to come across as anything other than goofy—no matter how giant he is, we’re more likely to chuckle than shiver.

Released back in 1951, The Thing from Another World no longer strikes us as particularly scary—not in its ideas, and not in its execution. We’re too far removed from the specific milieu that birthed it, and probably too desensitized by the decades of horror genre fare that have followed. It’s easy to understand why audiences at the time found it chilling, though. With its flying saucers and meddling scientists, Charles Lederer’s screenplay, loosely adapted from John W. Campbell Jr.’s seminal novella Who Goes There?, tapped into the intense technological anxiety and invasion paranoia that pervaded post-Hiroshima, post-Roswell America, weaving a claustrophobic yarn in which three conflicting institutions—the military, the scientific community, and the press—are forced to solve problems and survive together under pressure as a strange, hostile force closes in.

Even if the film’s ability to frighten us, or even creep us out, has diminished, its ability to charm and thrill us endures. Strip away the horror accoutrements, and what you’re left with is a contained collection of instantly endearing, thoroughly distinctive characters, who form a tightly structured network of interpersonal dynamics—something more akin to what Quentin Tarantino would call a “hangout film,” powered by ricocheting comedic dialogue and an exceptionally efficient visual engine. The human drama at the film’s core is generated by three primary players: Captain Pat Hendry (Kenneth Tobey), the pragmatic airman who resolves to destroy the creature after it’s inadvertently thawed from its stasis; Dr. Arthur Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite), the Nobel Prize-winning scientist who insists that the creature isn’t an enemy but a phenomenon, and should be revered, communicated with, and studied for its biological superiority (here you can see the seeds of Ian Holm’s Ash in Ridley Scott’s Alien, another admirer of a foreign species’ unsentimental purity); and Scotty, the everyman reporter who’s just looking for a picture and a story.

That the film has as much patience and empathy as it does for each of these individuals remains one of its finest qualities—there are no good guys or bad guys, only men with discordant principles, whose rivalry is infused with respect. Their actions are understandable, as are their miscalculations. Hendry’s use of thermite bombs to melt the ice that’s burying the flying saucer ends in an unexpected chemical reaction that blows the spacecraft to smithereens, but it’s the only logical and logistically viable strategy. And while another film might outright condemn Carrington’s protectiveness of the creature as the delusion of a madman, here he’s given the opportunity to emphasise that his position is at least partially compassionate: “It’s a stranger in a strange land. The only crimes involved were those committed against it.”

In its preoccupation with consummate professionals and their dueling philosophies, in its spatial sophistication, and in its fluid rhythm, the film is almost eerily reminiscent of some of the very best work in the oeuvre of Howard Hawks—which makes sense, of course. Aside from producing the project, Hawks is said to have been responsible for uncredited rewrites of the script, and handpicked the credited debut director, Christian Nyby, who’d spent years working for him as an editor on To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Red River. You’d assume the apprentice must’ve picked up a few things from the master, studied the crispness of the blocking and the acute attention to physical performance. But despite his undeniable grasp of visual grammar and deftness in the cutting room, Nyby’s accomplishments behind the camera have been a source of debate for as long as the film has existed. Speculation that Hawks was the film’s true director has been given credence by several cast members, including Tobey, who’ve said that Nyby merely contributed a handful of threads to Hawks’ overall tapestry—other cast members, meanwhile, maintain that Hawks merely acted as a consultant to Nyby, or directed only once every so often.

Ultimately, the sheer strength of the work largely eclipses such discussions. Regardless of authorship, the film is a paragon of propulsive filmmaking, boasting the same peerless, whiplash-inducing velocity of line delivery that makes Hawks’ classic screwball comedies so electrifying. Some of Hendry’s interactions—his telepathic relationship with his fellow airmen, his playful jockeying with Scotty, and his ribbing flirtation with his love interest, tough-talking secretary Nikki Nicholson (Margaret Sheridan)—wouldn’t seem amiss in Bringing Up Baby or His Girl Friday, films that move at such a blistering pace that they’re almost too quick for the human brain to process. The compositions that facilitate this speed are dense but never cluttered, often hectic but never incoherent, full of depth and shifting geometry. Within this controlled mayhem, the performances are sharp, precise, and instantly identifiable: Hendry is defined by his composed gestures and purposeful stride; Carrington by his rigid posture and laser beam gaze; and Scotty by his frustrated lurches and flailing limbs.

That level of stylistic rigour isn’t just rare in modern horror, which tends to favor muddier, murkier images in order to conceal other formal defects, but in modern filmmaking at large as well. We obviously still have a lot to learn from The Thing from Another World, which is why it’s unfortunate that despite its classic status, very few people talk about it in any context other than in unfavorable comparison with John Carpenter’s 1982 masterpiece, The Thing, the (sort of) remake by which it’s long been overshadowed, in which the creature isn’t a carrot but a shape-shifting nightmare. Conventional wisdom, it seems, pits the two films against each other, and judges the less viscerally impactful original to be obsolete. It’s better, I think, to see them as companion pieces, two variations on the same theme, one fizzy and one bleak, which produce equally entertaining results.

“The Thing From Another World” is currently available on Blu-ray from Warner Archive, and is available for digital rental and purchase.