This month marks the 10th anniversary of David Mamet’s mixed-martial-arts thriller Redbelt. In the intervening years, Mamet — the preeminent American playwright of his day, and one of the few screenwriters considered an auteur even when someone else directs his scripts — has been in something of an exile from Hollywood, one that seems only half self-imposed.

Since Redbelt, Mamet has directed only one other feature — the made-for-HBO true crime drama Phil Spector (2013), a baffling and morally repugnant film that seems inspired by Eli Cash in The Royal Tenenbaums: “Everybody knows that Phil Spector was guilty of murder in the second degree. What my film presupposes is…maybe he wasn’t?”

The shame of this is all the greater since Redbelt is one of Mamet’s most interesting and personally revealing films. It can be seen as predictive of Mamet’s turn away from the film industry and into the welcoming arms of reactionary identity politics.

Redbelt is a gripping (if occasionally awkward) mix of genres, several of which Mamet had come to perfect by that point. As much a con film as it is a fight film, it’s also a noir, a conspiracy thriller, a character study, a hero myth, and a modern-day samurai story. It is, above all, a look at the loneliness of honor in a corrupt world.

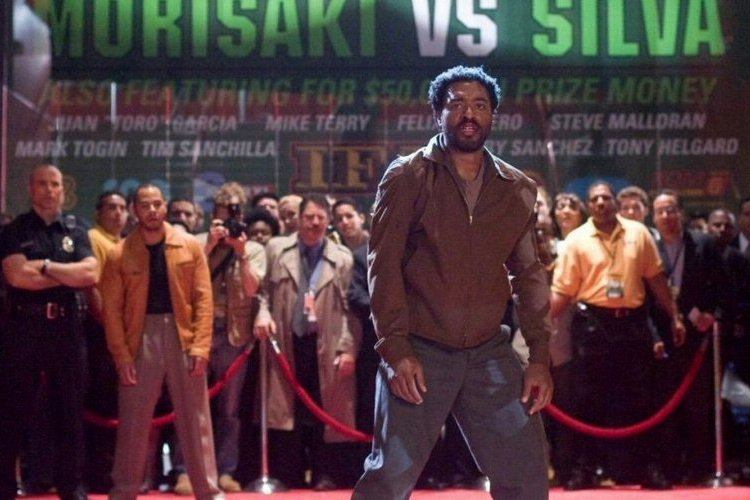

The film centers around Mike Terry (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a jujitsu instructor and Desert Storm veteran who specializes in training cops and soldiers. Although he married into Brazilian fighting royalty (his wife’s brother is a famous MMA champion), Mike himself abstains from professional competition. As he says:

“Competition is weakening. I train people to prevail. In the street, in the alley, in combat — the bodyguard, the cop, the soldier — there’s only one rule: Put the other guy down. You have to train in order to do that, and any staged contest must have rules.”

Mike is a man of principle and, for all the violence inherent in his vocation, ultimately a man of peace. Quiet, calm, and empathetic — the qualities that make him an excellent teacher also make him a lousy businessman. Overwhelmed by debt and behind on his bills, his dojo is failing, as is his marriage. (His wife sums up the problem when she asks, “How can you run your academy without money? You tell me, so I can do it without disturbing your purity.”)

Things begin to change for Mike after a series of seemingly unrelated events — the accidental discharge of a police officer’s service weapon inside his dojo, the promotion of a highly anticipated professional fight starring his brother-in-law, and a chance encounter in with an over-the-hill action film star (Tim Allen) — combine to briefly lift Mike from his financial and personal woes before ultimately wrapping him up in a miasma of criminal conspiracy and danger.

Along with its propulsively twisty plot (as much a staple of Mamet’s films as his famously profane dialogue), one of the things that makes Redbelt such an entertaining and rewarding experience is how adept it is at subverting viewers’ expectations. Despite the promise of its premise, there are only a handful of fight scenes, all of them quick and subdued. (Perhaps that’s why the movie came and went from theaters without much fanfare, despite its ostensible subject — MMA — being at the height of its popularity.) Just when the story seems set to enter the traditional formula of fight tournament films, Mamet swerves and delivers a shockingly simple and abrupt ending. There is a climactic fight scene, but like all of the fights in the film, it is not particularly “cinematic.”

This is intentional. Mamet, himself a long-time practitioner of jujitsu, has made the point that this style of fighting is not as inherently dramatic or easy to follow as boxing or kung fu. It mostly involves holds and counters, many of them occurring on the ground. As cinematic as they may be, haymakers and a flurry of spin kicks have little place in jiujitsu. While such adherence to realism may disappoint more bloodthirsty viewers, it also makes for a refreshing change of pace and stays true to the film’s core thesis, which Mike gives voice to several times:

“There is no situation you cannot escape from. There is no situation you cannot turn to your advantage.”

Redbelt is, ultimately, not so much a fight film as it is an escape film. Yet this does not lessen the sense of victory that comes at its conclusion, as stirring as any to be found in a Stallone or Van Damme movie. Mike’s final triumph feels exhaustive and transcendent, without ever coming off as easy, or even preordained.

The real heavy lifting is done by Chiwitel Ejiofor, who turns in what should have been a star-making performance. While his character remains something of a cypher (and at times can come off as a little bit of a Mary Sue), Ejiofor projects such a dignified bearing that he’s never in jeopardy of losing the viewer’s sympathy or devotion. That he manages to project such a tangible sense of moral goodness while making Mamet’s dialogue sound totally natural should earn him extra points. This is no small feat — Mamet’s own wife, Rebecca Pidgeon (a perfectly capable actor when left to her own devices) has never been able to achieve this, despite appearing in nine of his films. That this is Ejiofor’s first go-around with Mamet is amazing.

Ejiofor’s ability to make Mike Terry into a believable person is yet more impressive when you place the character in the context of Mamet’s latter-day obsessions. Where he made his name by writing about working-class losers and hustlers — the desperate salesmen of Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), the two-bit crooks of American Buffalo (1996), the sociopathic con artists of House of Games (1987) — Mamet eventually transitioned into telling stories about, as he put it in a Redbelt DVD interview, “the lonely man who must take his devotion into a very, very messy world.”

This describes not only Ejiofor’s fighter in Redbelt, but also Gene Hackman’s noble thief in Heist (2001) and Val Kilmer’s one-man army in Spartan (2004). Mamet-scripted films Ronin (1998) and The Edge (1997) also center around similar capital-H heroes. Those films all benefitted from having great actors flesh out his characters, because even though they are good roles (hence their ability to attract top-shelf talent) they are also clearly avatars for the type of person Mamet wishes he were (and possibly thinks he is). They are, ultimately, a kind of wish fulfillment.

This type of armchair psychoanalysis would be out of line with most filmmakers, but Mamet invites the interpretation. If you’ve ever seen him in interviews or read any of his books on writing and directing, you know that he goes to great lengths to sound like one of his own characters. He also often brings up his extensive interest in all things manly: jujitsu, woodworking, marksmanship, etc. And he’s made no secret of his disdain for those he considers spineless elitists: the press, politicians, and especially Hollywood insiders.

While everyone hates those people, Mamet’s antipathy feels particularly reactionary and one-dimensional, given that he came up in the theater world before making his fortune in Hollywood. When watching his later work, one can’t help but suspect that he’s working to overcome a deep sense of personal shame, especially in light of the hard right turn he took following the release of Redbelt in 2008 (which, appropriately, was also the year that Barack Obama was elected President).

Not long afterwards, Mamet — whom no one ever confused for a communist, even though some of his best known work does serve, intentionally or not, as brutal indictments of Reagan-era capitalism — would publish first an attack on progressive culture in an essay for the the Village Voice entitled “Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead’ Liberal,” and then an entire book, The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, in which he espoused his newfound ultra-conservative ideology.

This ideological conversion was hardly abrupt or surprising to anyone who had seen Redbelt. His loyalties are readily apparent within it, via his excoriation of Hollywood actors, producers, and fashion designers; and his hero worship of cops, soldiers, and athletes.

As it relates to the quality of the film itself, none of this matters. However, in looking at the dearth of quality work from Mamet in the time since, Redbelt can be viewed as a key moment of transition.

Mamet has long held that art should not be saddled with political ideology, yet he has continuously gone against his own dictum. During a Q&A on the Redbelt DVD, he cites the despairing example of movies made in Israel and Palestine, and laments how the only thing they ever explore is the conflict between themselves. This is a fair — if too broad and convenient — assessment, but one can’t help but scoff at the irony of Mamet being the one to make it. The film he attempted to produce following Redbelt was a modern-day retelling of The Diary of Anne Frank which sought to use the real-life Holocaust victim’s life as the template for a new story about “a contemporary Jewish girl who goes to Israel and learns about the traumas of suicide bombing.“

Almost as ridiculous is Mamet’s current defense of Donald Trump, not because it’s unthinkable — or important — that Mamet would support someone with Trump’s policies, but simply because the idea that the writer who has best conveyed the psychology of confidence scams would himself be taken in by the biggest and most obvious con artist in American history is almost too stupid to be believed.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Mamet has been absent from cinemas, as it seems like Hollywood can’t stomach him anymore than he can stomach it. That in that time none of his plays have been hits speaks to the adverse affect his political obsessions have had on his abilities as a writer (though of course he claims this is the result of a liberal media conspiracy).

Recently, there have been signifiers that Mamet might yet return to form. He released a Masterclass on screenwriting last year (if you’re at all interested in film writing you’ve no doubt had been targeted by its online ads), and one can only hope that by reiterating his advice on how to write a good, simple story, he himself remembers. And while he was recently replaced (by Scott Frank) on scripting duties for James Mangold’s forthcoming adaptation of Don Winslow’s crooked cop saga The Force — probably a wise choice, at least from a PR standpoint, considering the politically charged subject matter of the material — his newly published novel, the gangland epic Chicago, has earned the best reviews of anything he’s put out since Redbelt. These are all good signs.

On the other hand, Mamet has also announced that he’s currently working on a play about Harvey Weinstein. While his history of satirizing morally bankrupt movie producers of the Weinstein variety make him something of a natural fit for the subject matter, his often annoying penchant for empty provocation (see his previous take on political correctness, sexual harassment, and gender power dynamics Oleanna [1992]) make the prospect of such a play preemptively exhausting.

Whether or not we ever get another good Mamet film — hell, whether we ever get another Mamet film at all — we can put faith in the thesis of his last one of any worth: There is no situation you cannot escape from. There is no situation you cannot turn to your advantage.

Regardless of Mamet’s ability to work free from his self-inflicted debilitations as a writer/director, we’ll at least have Redbelt as something of a last stand for an artist who is equal parts fascinating and infuriating.