With the premiere of the Paramount Network’s Waco miniseries alongside continued controversy over Quentin Tarantino’s upcoming Manson-era film, there’s never been a better time to revisit the allure of the cult. But where real-life leaders like Jim Jones, Charles Manson, and David Koresh saw themselves as Messiah-like figures, most cult leaders in movies defer to a different power: Satan. From a filmmaker’s perspective, presenting an incontrovertible example of evil eliminates potential divisiveness while boiling the plot down to its basic parts.

The 1943 Val Lewton-produced horror film The 7th Victim exposes the Satanic doings of the Palladists, a group of business suit-wearing intellectuals bent on killing anyone who reveals their existence. The Palladists are bureaucratic; they don’t actually commit violence themselves, and compel followers to commit suicide. They’re hands-off, with little interest in attracting other followers. It’s possible the Hollywood Production Code, which prevented the disparagement of any religion or the promotion of wanton lifestyles, limited any further delving into the group itself.

The 1943 Val Lewton-produced horror film The 7th Victim exposes the Satanic doings of the Palladists, a group of business suit-wearing intellectuals bent on killing anyone who reveals their existence. The Palladists are bureaucratic; they don’t actually commit violence themselves, and compel followers to commit suicide. They’re hands-off, with little interest in attracting other followers. It’s possible the Hollywood Production Code, which prevented the disparagement of any religion or the promotion of wanton lifestyles, limited any further delving into the group itself.

The Palladists were reimagined in the 1968 Satanic horror feature Rosemary’s Baby. Where the earlier Palladists were older, tony members of the hoi polloi, the Satanists in Roman Polanski’s film are average elderly people. Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer’s characters, the Castevets, are underestimated as evil cult leaders. When Mia Farrow’s Rosemary discovers her child is the son of the Devil, the Castevets don’t respond with threats. They tell her she won’t have to become a member of the cult, and can instead luxuriate in the prestige that comes from being the mother of Satan.

The Palladists were reimagined in the 1968 Satanic horror feature Rosemary’s Baby. Where the earlier Palladists were older, tony members of the hoi polloi, the Satanists in Roman Polanski’s film are average elderly people. Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer’s characters, the Castevets, are underestimated as evil cult leaders. When Mia Farrow’s Rosemary discovers her child is the son of the Devil, the Castevets don’t respond with threats. They tell her she won’t have to become a member of the cult, and can instead luxuriate in the prestige that comes from being the mother of Satan.

The classy Satanists would be brought to an extreme in the 2008 French feature Martyrs, wherein a classy theological cult becomes obsessed with torturing a woman in order to make her a living martyr, and catch a glimpse of the afterlife. And 2015’s The Invitation sees a group of wealthy adults brought together after their friends join a chic-sounding cult that promises the removal of pain. In each of these instances, the cult is presented as a fad, accessible only to the wealthy or otherwise entitled.

The interest in demons extended across the pond. Night of the Demon (1957) follows a doctor, played by Dana Andrews, who attempts to solve a murder associated with a Satanic cult. Directed by Jacques Tourneur, a Lewton acolyte, Night of the Demon creates a similar world of academics attempting to solve a murder mystery first, a murder that just happens to have cultic connections. There’s never a need to extrapolate on the world of the cult or mine ambiguous consequences because there’s only one end result: the rampaging of a horrific, literal monster.

The interest in demons extended across the pond. Night of the Demon (1957) follows a doctor, played by Dana Andrews, who attempts to solve a murder associated with a Satanic cult. Directed by Jacques Tourneur, a Lewton acolyte, Night of the Demon creates a similar world of academics attempting to solve a murder mystery first, a murder that just happens to have cultic connections. There’s never a need to extrapolate on the world of the cult or mine ambiguous consequences because there’s only one end result: the rampaging of a horrific, literal monster.

By the 1970s, the cult world transitioned away from unleashing a literal embodiment of the Devil. With Vietnam and civil unrest worldwide, a demonic figure could no longer stand in for real-world horrors. Cults became more interested in working towards personal gain. (This was touched on briefly in Rosemary’s Baby; Rosemary’s husband offers her up as a vessel in order to fuel his stagnant acting career.) The 1975 Peter Fonda-starrer Race With the Devil sees a cult perform human sacrifice to garner undefined “magical powers.”

The Wicker Man (1973) contains many facets of the modern-day cult film. It follows an isolated community on the Edenic island of Summerisle. The group is sexually free, unashamed to engage in free love and expose their children to sexual matters. Their folkloric remedies of placing toads in mouths to cure a sore throat hearken back to colonial times. The staunch Catholic, Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward), is the outsider by which the audience experiences Summerisle, and many later cult movies have an outside observer act as an audience surrogate. The goal is either to prove to the audience the cult is evil/crazy/dangerous or, if the subject becomes one with the cult, to raise the stakes for the third act.

As the title implies, Summerisle’s “god” is a giant wicker man that houses a human sacrifice to secure a good harvest. Gone is the selfish desire for wealth and prestige; in its place is a need for survival and a simple solution to end their hunger. Though it’s easy to see the residents as hippies and Howie as the authority figure dealing with “these crazy kids,” the group represents an idealistic, and outre, means of ending world suffering. And unlike the previous cult films, The Wicker Man has a clear leader, Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle. He embodies the basic tenets of what would define the cult leader: intimidating, magnetic, dangerous to anyone who goes against him.

With the genre hewing closer and closer to reality, the movies eventually turned to real-life cult figures. Charles Manson received his first biopic in the 1976 TV movie Helter Skelter, while two movies recounted the tragedy of the Jonestown massacre: the 1979 Mexican exploitation drama Guyana: Cult of the Damned and 1980’s Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones. Jim Jones remains one of the more open targets in cult features to this day, as evidenced by Ti West’s 2013 drama The Sacrament, a recreation of the Guyana massacre for audiences uninterested in Google.

Coming only a few years after the events themselves, these movies skirt the line of bad taste, making an effort to present the “real story” while demonstrating how the two leaders took broken people and controlled them. By transitioning the cult film away from the vague “Satanist” to the real-life figures whose deeds left a string of bodies in their wake, audiences were reminded that they could easily become enthralled by these people — or, worse, their children could face indoctrination. The 1984 adaptation of Stephen King’s Children of the Corn follows a group of children compelled to kill their parents at the behest of a charismatic child-preacher named Isaac whose teachings take the Bible literally, the religious dogma of Christianity subverted.

Coming only a few years after the events themselves, these movies skirt the line of bad taste, making an effort to present the “real story” while demonstrating how the two leaders took broken people and controlled them. By transitioning the cult film away from the vague “Satanist” to the real-life figures whose deeds left a string of bodies in their wake, audiences were reminded that they could easily become enthralled by these people — or, worse, their children could face indoctrination. The 1984 adaptation of Stephen King’s Children of the Corn follows a group of children compelled to kill their parents at the behest of a charismatic child-preacher named Isaac whose teachings take the Bible literally, the religious dogma of Christianity subverted.

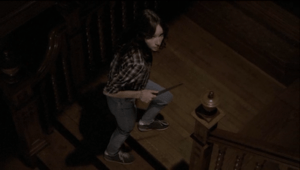

House of the Devil (2009) casts an eye toward a facet of history often forgotten: the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s. Ti West’s story of a babysitter who spends the night in the house of an unknown couple drew on the history of Satanists in cinema. The Ulmans (played by Tom Noonan and Mary Woronov) are an older, unassuming couple in contrast to Jocelin Donahue’s young, chipper babysitter, Samantha. The increasing terror that Samantha (Jocelin Donahue) experiences alone in the house leaves just enough room for the audience to question whether these people are in a cult or whether Samantha is just overreacting — mimicking the feelings of many who assumed Satanists were living next door to them. And much like the beginnings of the religious cult in cinema, House of the Devil lacks a tangible leader, instead bringing in a Rosemary’s Baby-esque twist involving the devil. Satanists also briefly returned in the 2000 film Bless the Child, wherein a group of devil-worshippers attempt to possess the mind of a small child presumed to be a conduit to God.

House of the Devil (2009) casts an eye toward a facet of history often forgotten: the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s. Ti West’s story of a babysitter who spends the night in the house of an unknown couple drew on the history of Satanists in cinema. The Ulmans (played by Tom Noonan and Mary Woronov) are an older, unassuming couple in contrast to Jocelin Donahue’s young, chipper babysitter, Samantha. The increasing terror that Samantha (Jocelin Donahue) experiences alone in the house leaves just enough room for the audience to question whether these people are in a cult or whether Samantha is just overreacting — mimicking the feelings of many who assumed Satanists were living next door to them. And much like the beginnings of the religious cult in cinema, House of the Devil lacks a tangible leader, instead bringing in a Rosemary’s Baby-esque twist involving the devil. Satanists also briefly returned in the 2000 film Bless the Child, wherein a group of devil-worshippers attempt to possess the mind of a small child presumed to be a conduit to God.

The cult has taken on an increased prominence in the last decade, possibly due to the religious and political divides the separate us. The emphasis on devil worship still stands, in features like Drive Angry and the “Safe Haven” segment in V/H/S 2. Others have a tacit awareness of specific groups without naming them. When Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2012 feature The Master came out, audiences were excited about — and disappointed in its ultimate presentation of — the controversial religion of Scientology. Kevin Smith’s 2011 horror feature Red State featured a religious group whose hatred of homosexuality was a sly critique of the Westboro Baptist Church. The mere knowledge of reality acts as a means of enticement to watch.

Real-life cults remain a male-dominated medium, and when movies present female cult leaders, a sexual component tends to crop up. Sound of My Voice (2011) introduces Maggie (Britt Marling), a woman who touts herself as being from the future. Her cult doesn’t espouse violence but a cleansing of body and soul. She doesn’t control with physicality but is adept at mental manipulation. This comes in handy when a male outsider, intent on exposing her as a fraud, falls for her.

Real-life cults remain a male-dominated medium, and when movies present female cult leaders, a sexual component tends to crop up. Sound of My Voice (2011) introduces Maggie (Britt Marling), a woman who touts herself as being from the future. Her cult doesn’t espouse violence but a cleansing of body and soul. She doesn’t control with physicality but is adept at mental manipulation. This comes in handy when a male outsider, intent on exposing her as a fraud, falls for her.

Faults (2014) is part of the “cult deprogramming” sub-genre, with Mary Elizabeth Winstead’s Claire revealed as the leader of a cult. Jane Campion’s Holy Smoke (1999) also sees a male deprogrammer (Harvey Keitel) fall under the spell of a cult member (Kate Winslet). Their sexual relationship opens the door to a discussion of gender and how religion interacts within it. And the 2011 drama Martha Marcy May Marlene put the cult member as the outsider, with Elizabeth Olsen’s Martha attempting to deprogram herself after escaping a Manson-esque personage played by John Hawkes.

This is just a glimpse into the allure of the cult. All of these films attempt to showcase the cult as a false promise that claims to solve problems but only delivers pain and sadness. Whether the devil is unleashed by the end or not, the cult remains a fascinating film figure that we haven’t yet seen the end of.

Kristen Lopez awaits her ascension in Sacramento.