The release of Andrew Dominik’s Blonde, a baroque dramatization of the life and stylized persona of Marilyn Monroe, has inspired a deluge of concerns from many critics and fans of the actress. For some, it will always be too soon to make entertainment out of Monroe, the late icon who has been our primary representation of Hollywood tragedy and exploitation for well over five decades. Surely to rehash the tragedy of her life for commerce will simply repeat the mistakes of the past. The fear from Monroe fans is that Blonde will focus more on the agony than the circumstances that created it, another opportunity for the industry to cash in on a figure who they already bled dry. It’s certainly a tough bind for any filmmaker. Is any project intended for mainstream and profit-driven purpose capable of fully presenting the abject horror of this parasitic system and the countless people who have been engulfed by it? Perhaps Bob Fosse can provide a guiding hand.

Star 80 dramatizes the short life and horrific death of Dorothy Stratten, a Canadian model who sharply rose to fame by becoming a Playboy centerfold, only to be violently murdered by her husband, small-time pimp Paul Snider. The incident sent reverberations through Hollywood and was instantly elevated to the level of city-wide lore, the ultimate cautionary tale for a new era of fame. For his final film as a director, Fosse wasted no time in bringing Stratten’s story to the big screen, with the movie premiering a mere three years after her death. For him, there was an urgency to this narrative and it needed to be told as soon as possible.

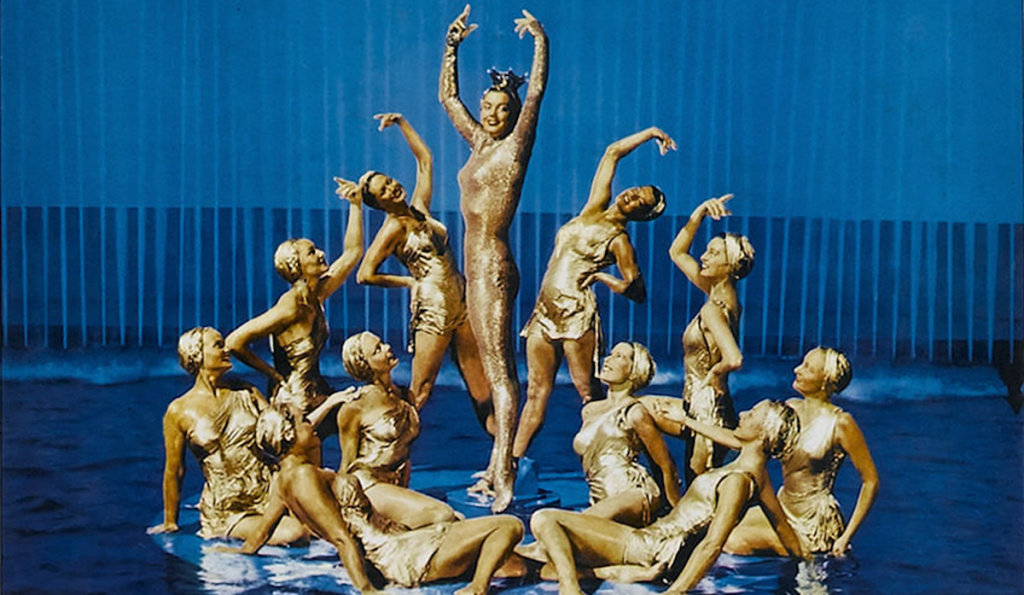

Fosse, a man who conquered both Hollywood and Broadway and whose influence remains on both coasts to this day, was keenly aware of the soul-sucking consequences that followed a hunt for fame and fortune. Each of his five films tackle in some manner the enticing pain of that descent into oblivion. Cabaret revels in the blind escapism of Weimar-era debauchery on the eve of the Nazi takeover. Lenny shows an iconic comedian’s free speech battle against the establishment to be a futile fight that destroys its subject and all who surround him. His magnum opus, All that Jazz, is so achingly autobiographical, detailing Fosse’s own addictions and obsessions with unflinching candor and revealing how not-so-great a time he was having with his own success. Somehow, Star 80 gets even darker than a movie that ends with its own director in a body bag.

Stratten’s murder is seen as a dire inevitability, a symptom of a city-wide sickness that requires sacrificial lambs of intense youth and beauty, and total lack of autonomy. Theresa Carpenter’s Village Voice profile of Stratten, which provides the basis of Star 80, cruelly described the young woman as someone who “floated along like a particle in a solution.” Indeed, she often seems like a secondary character in her own story, overwhelmed by her manic Svengali husband (played by a terrifying Eric Roberts as a slasher villain crossed with a failed pick-up artist), the smarmy business-minded leering of Hugh Hefner, and the love of Aram Nicholas (an extremely thinly veiled stand-in for Peter Bogdanovich), an older director whose earnest gaze carries an air of familiar objectification. While Stratten’s presence often feels diminished to the detriment of the film, Fosse compensates with a brutal confession: all men, to varying degrees, hate women, and if you were to know the full extent of that, you’d never recover.

Carpenter and Fosse both come to the same conclusion about Snider, Hefner, and Bogdanovich/Nicholas: they’re all leeches cut from the same cloth. Snider, a violent weirdo who doesn’t fit into the gloss of Hollywood that he pushes Stratten towards, is just the small-time version of Playboy’s beloved king. When Hefner is shown in his fancy office looking over a new selection of women for the magazine, it’s contrasted with the grisly scene of Stratten’s murder. There’s no way, according to Fosse, to placate such men, or to even play with them on an even field of power. Women like Stratten, more likely to be referred to as girls (‘young and wholesome’ is how Hefner likes them), are essentially livestock in this world.

As the kind, naïve, and trapped Stratten, Mariel Hemingway is heart-breaking. Bearing an eerie resemblance to the late model, she works overtime to appease those who she knows will hurt her. It’s really the only option available to her. Even at her most innocent, she’s hyper-aware of how little control she has over her own life. Carpenter’s profile seemed disdainful of Stratten’s lack of power, yet it’s that stripping of autonomy that feels so honest. None of the men in her life view her as a person, so why would her suffering matter to her?

Star 80 is not a film to like. It’s often tough to appreciate and plenty of people see it as worthy of condemnation. For decades, it’s inspired discourse around the ethics of portraying this level of exploitation and whether or not such things can be done without endorsing or glorifying in such pain. Star 80 works because it understands that, in order to truly show the decay of patriarchal rule, you must take the story to its harshest yet most logical conclusion. Dorothy Stratten died by that hand and yet, as Joan Didion famously wrote about the Tate-LaBianca murders, nobody was surprised.

“Star 80” is streaming on HBO Max and is available for digital rental or purchase.