I hadn’t attended the Sundance Film Festival in person since 2023, finally priced out of the trip to Park City by the seemingly unstoppable cost of travel and (especially) housing, particularly when online options were available. But the news that this year’s edition would be the festival’s last in its home base of Park City, Utah, coupled with the recent passing of guiding light Robert Redford, pushed me to take the trip, finances be damned, and I’m glad I did. There’s a sense of joy at this festival, a feeling of everyone sorting through their memories (moviegoing and otherwise).

Of course, there are new movies to see and new memories to make, and many of them are special as well. You will occasionally hear the hipper-than-thou dismiss one indie or another as a “Sundance movie,” and the shorthand is pretty universally understood: the kind of navel-gazing, small-truths indie that tends to do very well up here in the mountains, and very little anywhere else. But the thing is, sometimes Sundance movies are pretty good, and if you’re not going to see and enjoy them at Sundance, then for God’s sake, when and where else? All of which is a roundabout way of saying that Ramzi Bashour’s Hot Water is a Sundance movie — a Sundance road movie, even, a notable subset — mellow, laid-back, and lived-in, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Lubna Azabal is deeply sympathetic in the leading role of a middle-aged Lebanese single mom, mostly miserable teaching Arabic to white kids at an Indiana college, whose troubled teen son (Daniel Zolghadri) gets expelled for fighting and needs to go live with his estranged father in California. The story beats don’t go anywhere unexpected (aside from some unfortunately broad nudist humor), but the performances are winners; Azabal turns a purely reactive character into something active and alive, Dale Dickey is (as ever) a joy in her brief but memorable appearance, and Zolghadri is a real find, his mixture of charisma, restlessness, and recklessness legit recalls Mark Ruffalo in You Can Count on Me — another “Sundance movie,” for the record.

Bedford Park plays in the same key, a movie filled with high-stress situations, but one that barely speaks above a whisper. Moon Choi and Son Sukku (both terrific) star as a pair of unlikely would-be lovers, and writer-director Stephanie Ahn is willing to take her time, letting them soften each other up, let their guards down, and finally make a tentative connection. She’s got a good ear for dialogue, the kind of everyday speech where people rarely say what they really mean, and she shows a welcome sensitivity to actors; she’ll catch a fleeting reaction or a split-second of time alone that tells you everything.

The picture feels personal, handmade — so much so that it’s a real shame that she’s loaded up with too many subplots and side characters to grapple with and pay off in the third act. It’s best when it sticks to its center: Two people who are both a little broken, in their way, but can see something in the other that maybe they can help fix.

The most jaw-dropping announcement of this year’s Sundance slate was Once Upon a Time in Harlem, the (to me, at least) heretofore unknown project that the late, great documentarian William Greaves shot (but never completed) well before his death in 2014. It seems that in August 1972, he held a cocktail party, “a gathering of artists and intellectuals, the living luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance” at Duke Ellington’s apartment, and filmed what happened there. There was an astonishing accumulation of wisdom in those rooms, “miles and miles of memories,” as photographer James Van Der Zee puts it, but Greaves doesn’t leave it there. The party is the framework, the main event, supplemented by individual interviews to provide a more complete oral history of the Harlem Renaissance — and the deeper it goes, the less it becomes that than the wider cultural and social history of Black America.

The conversations he captures are thoughtful, often spirited, and sometimes contentious discussions of the issues that caused friction at the time (integration vs separatism, cultural vs political, men vs women, Dems vs Republicans), and still do; these wounds are easily reopened (“THAT is your OPINION”), and many of these these debates that raged for half a century have continued for a half-century more. Greaves asks questions and perhaps eggs them on a bit, and the resultant, marvelous film is very much in the form of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (specifically, its inspired use of split screen). On one hand, this all took place a long time ago. On the other, Eubie Banks casually notes, “my mother and father were slaves,” a sharp reminder that we are not as far removed from the lowlights of our history as we’d like to think.

No one’s more tired of the fawning celebrity bio-doc than I am, so it gives me immense pleasure to report that Broken English, Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s investigation of the mythos of Marianne Faithfull, is an inventive delight. And “investigation” really is the right classification, tongue-in-cheek though it may be; the clever premise is that Faithfull is the first subject of the “MINISTRY OF NOT FORGETTING,” where her life and career are examined by a team of researchers, interviewers, and an Overseer (played, of course, by Tilda Swinton). The set-up allows the filmmakers to peer at her through all sorts of different lenses, which is a smart approach. It also allows them to avoid most of the traps of the entertainment bio-doc.

George Mackay is a charmer as the main interviewer, showing the singer, songwriter, actress and all-around icon scores of old interview clips (of herself and others), performances, photos, clippings, liner notes, and more, for her off-the-cuff commentary (“The night before I did this interview, Mick and I had taken LSD”). It’s a device that works, because she is a) so witty, and b) so utterly intolerant of bullshit. And neither is the movie, which is spirited and thorny, granting her the agency and complexity she deserves, and when she notes, near the end of the picture, that “I hope I’m not too broken,” it’s sort of overwhelming; you feel, in that moment and throughout, a sense of relief that she somehow managed, in spite of everything, to find her way through.

Luis Valdez was an honest-to-goodness innovator, “the Shakespeare of Chicano theater” as Luis Garza puts it, but alas, the documentary portrait American Pachuco: The Legend of Luis Valdez isn’t nearly as boundary-bending as its subject. Director David Alvarado does come up with one clever device, transporting the “Pachuco” narrator of Valdez’s beloved Zoot Suit into his film as a narrator (voiced, as in Zoot Suit, by Edward James Olmos), laying things out and commenting on the action, though Alvarado ends up leaning on it a bit too heavily by the end to spell things out.

Which is not to say that it doesn’t have worth as a conventional documentary. Alvarado thoughtfully explores Valdez’s intersections with, and artistic reactions to, the Latin American story, and shares fascinating stories and electric footage of the “Workers Theatre” he created and ran for cousin Cesar Chavez during the United Farm Workers strike, which transformed into the theater of social commentary and satire which would become his legacy. But they fumble the ball at the end, barely acknowledging his career after the triumph of La Bamba — why was that his last theatrically released film, one might ask, and one will find no answers here. For much of its runtime, American Pachuco is energetic and engaging, if fairly boilerplate; it opens with an American Masters logo, an appropriate destination for it. And don’t get me wrong, I love American Masters. But I watch those at home, not at film festivals.

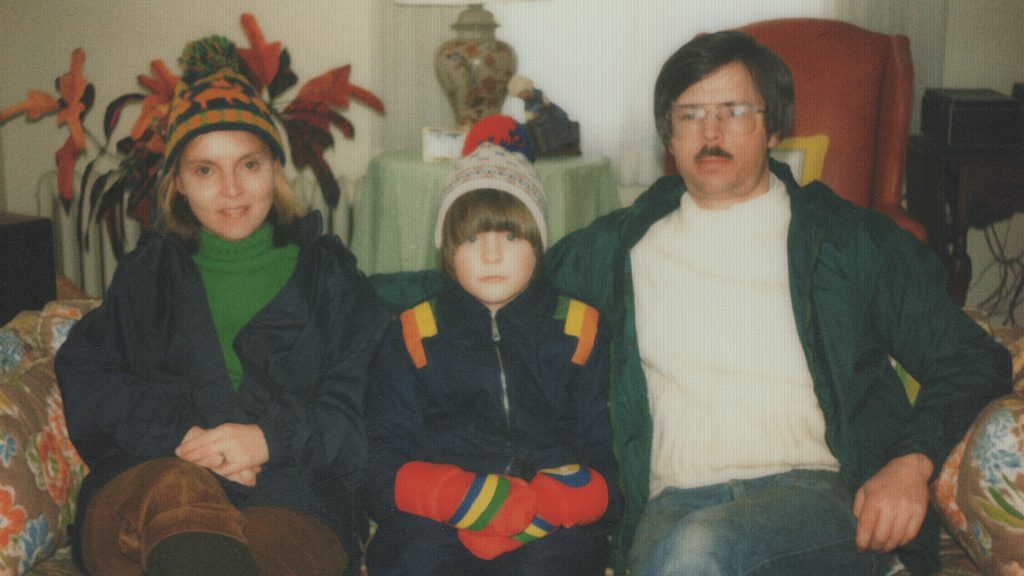

To that end, the question posed by Paralyzed By Hope: The Maria Bamford Story is a simple one: Can you tell the story of such an unconventional subject within such a reliably conventional format? Maria Bamford is, as many have said before, something of a “comic’s comic,” a comedian whose act lives somewhere in the space between stand-up and performance art, and whose struggles with mental illness have provided copious fodder for said act. “When I was nine or ten,” she confesses early on, “I remember thinking there was something desperately wrong with me,” and she has spent her life and career picking at that scab.

Directors Judd Apatow and Neil Berkeley’s documentaries on George Carlin and Mel Brooks are entertaining but fairly straight-ahead affairs, motored by the whiz-bang energy of their subjects. Paralyzed By Hope is something quite different, dealing with somber topics (Intrusive thoughts! Suicidal ideation! Anxiety! OCD! Serious shit!) without pushing too hard for “levity” — at least beyond what’s provided by clips of Bamford turning it into material. (They eschew a musical score, which sounds like a small thing, but makes a big difference in tone and feel.) They tell her story with emotion but not sentiment, and that’s the right call. And by the end, when Bamford insists, “I am not a good time,” you may not be so sure.

I’ll own my biases: I may not be the ideal audience for The Last First: Winter K2, a documentary about a bunch of “extreme mountaineers” who attempted a wintertime summit of K2, “the most dangerous mountain in the world to climb” in the summer. Sorta-spoilers: several of them died, and left loved ones behind in the process, and I’m sorry, that’s inherently difficult to sympathize with. Say what you will about spending too many evenings getting stoned and watching kung-fu movies, but you’ve never once heard of someone freezing to death or falling to their death while doing that.

So perhaps it speaks to the skill of director Amir Bar-Lev (The Tillman Story) that his film about what happened on the mountain in the winter of 2021 is so riveting. It’s a fairly straight-forward account, mixing after-the-fact interviews with copious footage from the climbs (because everyone has cameras, or even videographers, so they can post it all on socials), but Bar-Lev also explores the motivations (some sketchy, all colliding) of those involved, weighs the heavy burden of nationalism and even wealth inequality, and does so with clarity and intelligence.

One of the running themes of Judd Ehrlich’s Jane Elliott Against the World is the difference between a teacher (who teaches students to memorize facts and figures so they can score well on tests) and an educator, because the Latin root words of “educate” translate to “to lead out” — specifically, to lead out of ignorance. Jane Elliott is a tough old broad, an 89-year-old author, activist, and, yes, educator, who was radicalized by the murder of Martin Luther King and began teaching, in a rural classroom in Iowa, the “ blue-eyed, brown-eyed exercise,” a vivid illustration of the insidiousness of racial bias.

She first taught it to her class of third graders, and then to other groups of kids, educators, and adults, for decades to come. Ehrlich’s film is partly that history, illustrated with excellent archival footage, and partly an illustration of how it’s not history at all; he details how she is leading the fight against the Trump-adjacent Christian nationalists who have taken over the school board in her grandkids’ hometown of Temecula, California — this ridiculous and insidious notion that you cannot honestly teach U.S. history because it will make white kids “feel bad.” It’s not a total valentine; Ehrlich doesn’t paper over her flaws, most notably her strained relationship with her family, and wounds her children still nurse over how she neglected them for the work. The complexity matters, keeping Jane Elliott Against the World from becoming a typical rah-rah activist doc. She’s an inspiring subject — she makes you want to keep fighting, because you know she always will.

Buddy opens with an episode of It’s Buddy, a ‘90s children’s show hosted by a Barney-style soft and lovable hero, a “unicorn from a magic land” who teaches the kids who hang around his clubhouse life lessons via games and songs. Unsurprisingly, since director and co-writer Casper Kelly is responsible for Too Many Cooks, the aesthetics are bang-on for ‘90s children’s television: garish production design, flat and ugly videography, written-in-five-minutes songs. Unsurprisingly, since this is a Midnight selection, it moves into creepy, unsettling territory; a kid resists Buddy’s pleas to dance, screaming “LEAVE ME ALONE, I HATE YOU,” and at the episode’s end, one of the kids spots her resistant castmate’s blood-stained book in the trash.

I assumed this was just the set-up, but more episodes follow, 30 minutes of them, and while it’s a clever conceit — a paranoid thriller within a bunch of kids show episodes, a clever act of recreation and subtext — a reasonable viewer will wonder how they can sustain that for 95 minutes? With some difficulty, it turns out. Kelly shifts to a completely different narrative in a more conventional style, featuring Cristin Milioti acting her heart out as a normal mother suddenly overwhelmed with a sense of total terror, and then merges them, not entirely successfully. Kelly can’t quite manage to walk the tricky tightrope between darkly funny and unpleasantly disturbing. Black comedy is hard, after all; steering into pathos, even moreso. Ultimately for all of its ambition, all of its shots at innovation and character-building, Buddy is just a slasher riff, and a fairly middling one. I admire its audacity more than its execution.

A more successful entry among the Midnight selections, writer/director Adrian Chiarella’s Leviticus is built from a dizzyingly smart central premise: its monster is summoned by, in essence, gay conversion therapy (staged here like an exorcism), and appears to those it hopes to kill by taking the form of the one they love. In this case, that’s Naim (Joe Bird), new kid in an isolated religious community, who finds himself drawn to the charismatic Ryan (Stacy Clausen).

The clever structure introduces them after a genre-heavy pre-title scene, lending sinister undertones to what seems, on its surface, a seemingly disconnected queer coming-of-age story. But Chiarella is exploiting one of the most durable tropes of horror — nothing is more terrifying than religion — and making savvy choices about what we see and know, and when. Once the premise is established, there’s a slight sense that they don’t quite know where to go, and when a picture is this finely tuned and specific, it’s a bummer to resort to generic jump-scares. (Also, I deeply resent this movie for making me aware that Mia Wasikowska is now old enough to parent a teen.) But there’s a lot to chew on here, and Chiarella and his charismatic stars are ones to watch.

The Sundance Film Festival runs through Sunday; our next dispatch will publish Thursday.