The Sundance Film Festival sees dozens of new indie dramas every year that could be compared to Lovesong. It’s practically a game for critics: can you fill your Sundance bingo card by watching enough low-budget films with naturalistic dialogue, little plot, a queer element, and emotions left unspoken? Add a tragic twist and you’ll have every studio in town overbidding for distribution rights. The 2016 drama Lovesong, directed by So Yong Kim, fell under the radar after its Sundance premiere, yet another indie film that couldn’t keep up with the likes of Swiss Army Man and The Birth of a Nation. That’s a shame, because here is a deftly told and achingly real story of unfulfilled love that deserves a far greater audience.

Sarah, played by Riley Keough, is a stay-at-home mother whose husband travels for work and often seems disinterested in her concerns when he contacts his family via jittery Skype calls. She calls her best friend Mindy (Jena Malone) for help, even though they haven’t seen one another in years, and they depart for a road trip that reveals their deep-seated feelings for one another. They reminisce about a shared sexual experience from their college days, and soon the gates are opened once more for them to embrace that underlying passion. Yet it’s clear to both Sarah and Mindy that nothing could ever come of this. One of them is married and the other is engaged. Life has to go on.

Kim’s work shines in the near-liminal spaces that connect humans to one another, those moments that cannot or shouldn’t be articulated through mere words. Unrequited love is one thing, but to know that it’s reciprocated yet cannot and should not be is a tougher experience to nail down. Sarah and Mindy’s relationship in its various forms evolves so organically that it’s impossible to imagine it going any other way. Kim brought this ephemeral quality to life perhaps most potently in her sophomore film, 2008’s Treeless Mountain, a South Korean drama about two young girls who struggle to understand why their mother has left them. Viewed through the increasingly hardened gaze of a six-year-old forced into premature adulthood, the film allows Kim to dig into the uncomfortable realities of trying to exist when you’re forcibly disconnected from those who are supposed to help you become yourself.

The protagonists of Lovesong are older, somewhat wiser, but no less troubled by this experience. Sarah and Mindy can’t allow themselves to get into a giant confrontation or any sort of movie-friendly dialogue that could offer them some much-needed catharsis. The best thing to do, the proper thing, is to conceal it all for as long as possible, to mask one’s unbearable sadness as something else. The closest Sarah gets to such a moment of release is in seeing Mindy marry a man she does not seem to adore. She cries, and Kim focuses the camera on her, as we see her emotions turn from pain to acceptance, all under the guise of joy for her best friend. It might be the most beautiful moment of Keough’s varied career.

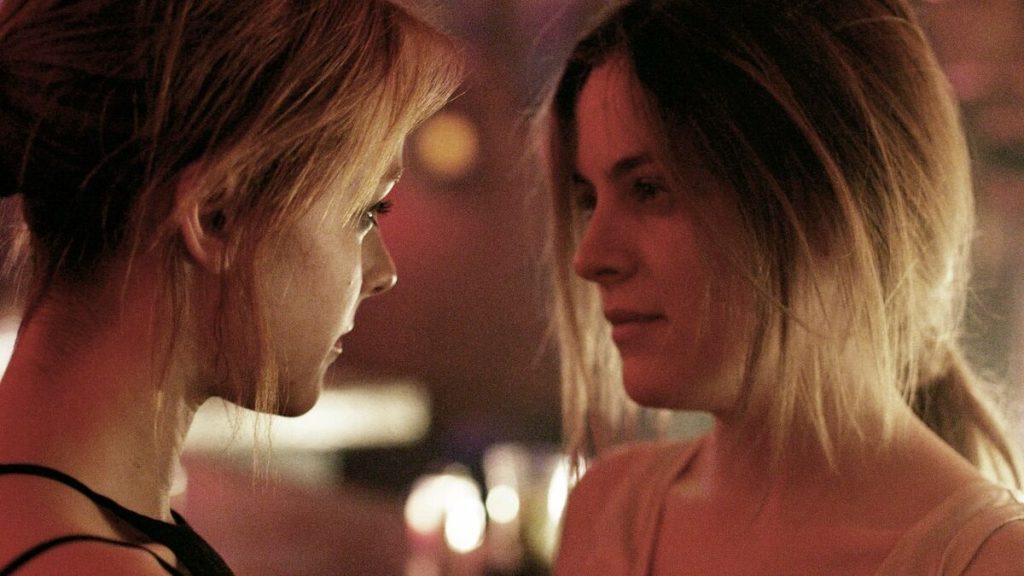

Lovesong is, of course, about love, but not one specific kind. The love that is supposed to bind husband and wife for a lifetime is seldom as neat or guaranteed as pop culture loves to make it. For Sarah, her marriage to a distant man seems like an obligation both have become increasingly disinterested in maintaining. Mindy’s nuptials seem to baffle everyone, including her mother. It’s just something she’s doing, which doesn’t seem to bode well for the marriage itself. Whatever love both women feel for their respective husbands, it’s obvious that it pales in comparison to the love they share. It’s partly romantic but more about a deep-seated connection that not even their legal partners could disrupt. The intimacy of their interactions, from glances to holding of hands to the eventual kisses, unfold naturally – to the point where you, the viewer, often feel like an intruder. And their love will remain in place even if they never see one another for years at a time. They may not ever talk about it, may never fully acknowledge or understand what it is that they have, but what goes unspoken is not unfelt.

This is a film of hope, one that ends on a bittersweet note but not one devoid of optimism. Perhaps Sarah and Mindy will eventually end up together. Maybe they won’t. For So Yong Kim, it barely matters. What was important to show was the love itself, and how it never goes away. The blunt ache of Lovesong more acutely captures the true power of love than a million Hallmark cards ever could. It should be such a cliché to tell the story of the beauty of lost love over never having loved at all, but Kim and Lovesong eschew all of that in favor of something far more real. Maybe that’s why it never got out of the Sundance bubble. How do you categorize something that is at its best in the spaces in-between?

“Lovesong” is available for digital rental or purchase.