As the unbearable discourse surrounding sex scenes in film reaches its latest month of tedium, the Criterion Channel has mercifully offered us a breather in the form of a season dedicated to the joys of the erotic thriller. Nestled among the expected titles, like Body Double and The Last Seduction, is Paul Schrader’s foray into the genre, The Comfort of Strangers.. But to categorize it as a traditional erotic thriller would be a mistake. It’s the glacial subversion of the form that went unappreciated in the era of skin and sleaze.

Schrader has never avoided sexuality in his films – indeed, it’s as defining a quality of his work as spiritual crises and the consequences of violence. He can make a case towards being the purveyor of all-American cinematic sleaze, albeit through a more sex-negative lens than many of his contemporaries. It’s not that he dislikes or fears sex so much as he sees it as an inevitable route towards oblivion, from the ways that desire dooms his heroine in Cat People to George C. Scott’s descent into the unregulated hell of ‘70s porn in Hardcore.

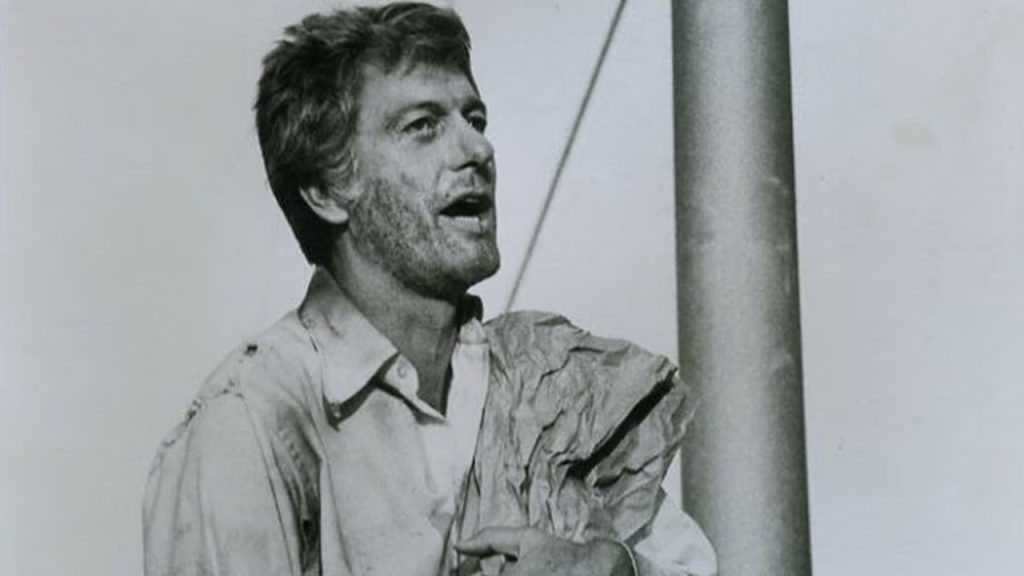

The Comfort of Strangers shares more DNA with its Venetian contemporaries, Death in Venice and Don’t Look Now, than, say, the films of Joe Eszterhaus that came to wholly define the ‘90s erotic thriller. Based on the novel by Ian McEwan, with a script by Harold Pinter, the story follows a young couple on holiday in the city, Colin and Mary (Natasha Richardson and Rupert Everett), who become embroiled in the curious unease of an older pair (Christopher Walken and Helen Mirren) whose dynamic raises questions about their own relationship.

The crumbling opulence of Venice, its graffiti-covered walls adorned with violent protest posters, reflects the conflict of the old world and new that dominates this quartet of troubled lovers. Richardson and Everett wander, half-lost, through the streets of the city, often entirely alone in this tourist hotspot as Walken watches from them a distance. This is a place steeped in menace, the shadows of Visconti and Roeg’s films looming heavily overhead for Schrader and Pinter. The latter’s notoriously spare dialogue avoids thematic bluntness but retains the unease of McEwan’s novel, particularly in how Walken’s Robert talks about his misogynistic past and violent father with the younger pair like it’s a whimsical ice-breaker.

There’s not much sex in The Comfort of Strangers, especially when compared to the giddily orgiastic fare of Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct. The burn is slow to the point of soporific, with moments such as Colin’s nakedness in bed feeling incidental until you realize just how calculated everything truly is. Mirren’s Caroline, an evidently troubled Canadian woman dealing with chronic pain, asks her visitors about their personal life with such casualness that they cannot help but acquiesce to such questions. This new attention adds pressure to the tiny fractures that have permeated their long-term relationship, previously vocalized not through screaming fights but moments of passive-aggressive malaise amid lovers’ strolls through the city.

Mary repeatedly expresses a desire to see the “real Venice”, a change from their last trip to the city that focused on the outsider-friendly experiences. The promise of a vacation for many is the respite from reality, even as we claim to seek something more authentic than those other silly tourists. When Robert offers to treat them to dinner at an authentic Venetian spot, he takes them to his rundown bar which seems to cater mostly to men. His home, evidently monied and lavishly decorated, reeks of colonialist stylings. Even as they are repulsed by the older couple and what seems to be an abusive dynamic between them. Colin and Mary return to their web, enthralled by the worldliness they embody that seems to be “real” to this city they superficially adore. Their commitment to politeness that keeps them in danger is so hilariously British that it’s no wonder they were preyed upon so easily by Robert and Caroline.

When things finally boil over into murderous eroticism, Schrader remains remarkably restrained. Little blood is spilled, unlike the climax of the novel. The comfort of strangers of the title, that optimistic promise of kindness from others, reveals itself to be naught but a sick game for personal gratification. Robert has stalked them through the city, mostly unseen, but when he is visible he casts a figure as shudder-inducing as the red coat in Don’t Look Now. The angelic form of Rupert Everett at his prettiest is reduced to a corpse who twitches on the floor as Robert and Caroline fuck, engorged by his death, and Mary watches on unable to help. What could be more decadent than the destruction of beauty?

Schrader understands the beautiful trap of sexual manipulation. His cynicism finds a keen match with Pinter and McEwan, although, as is so often his forte, he can’t help but want to have his cake and eat it too. Beauty is perverse and vice versa, and the pleasures of unfettered sensuality come with too many strings attached for Schrader to make something so simple as an erotic thriller. As with all things in life, it will, sooner or later, rot away.

“The Comfort of Strangers” is streaming on the Criterion Channel as part of its “Erotic Thrillers” program.