As I’ve mentioned in previous articles, the 1980s weren’t a great time to be a female. The end of second-wave feminism in the ‘70s left many Americans believing equality among the sexes was “solved.” As author Susan Faludi described, there was a backlash that sought to undo everything the Women’s Libbers had pressed for by creating a pop-culture world of fear-mongering and outdated myths to scare women back into domesticity.

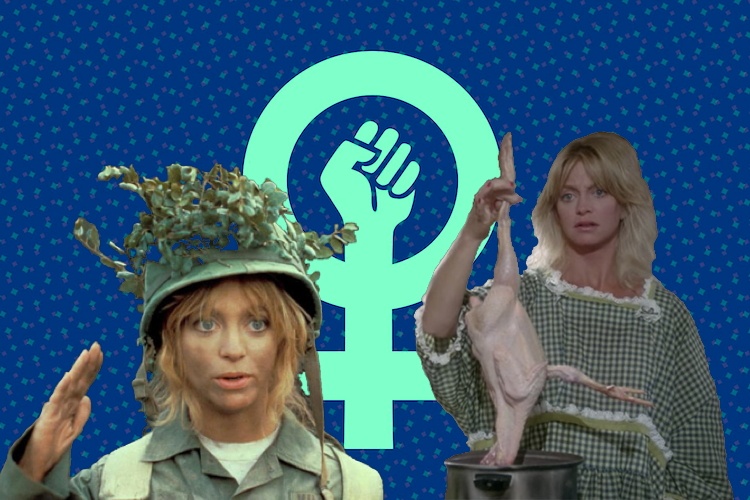

All of this is perfectly encapsulated in two films that bookended the decade: Private Benjamin (1980) and Overboard (1987), both starring Goldie Hawn as two very different women, both aimed at showcasing the “modern” woman of the era. One falls perfectly into where the ‘70s ended and the dreamy future of feminism, and the other is a reminder of where women ended up.

Private Benjamin tells the tale of Judy Benjamin, a sweet-natured daddy’s girl whose world is upended when her husband dies on top of her on their wedding night. Depressed and frightened about her future, she enlists in the Army. Initially shocked at the harsh realities of what the Army entails, the newly minted Private Benjamin begins to grow up and learn how to take care of herself.

Private Benjamin tells the tale of Judy Benjamin, a sweet-natured daddy’s girl whose world is upended when her husband dies on top of her on their wedding night. Depressed and frightened about her future, she enlists in the Army. Initially shocked at the harsh realities of what the Army entails, the newly minted Private Benjamin begins to grow up and learn how to take care of herself.

Private Benjamin situates its heroine as the active agent in her own story. Judy is introduced as an overly made-up woman who’s blindly followed the path laid out for her, getting her MRS degree by marrying the bland Yale Goodman (Albert Brooks), a man whose name underscores an Ivy League pedigree and the overall tone that he’ll “take care” of Judy. But Yale’s death leaves Judy adrift. If she’s not a man’s daughter, girlfriend, or wife, who is she? These are questions many women grappled with in the face of an escalating divorce rate and burgeoning independence.

Judy’s traditionally feminine character clashes with the male-dominated world of the military. That’s poignant considering 1980 saw the first graduating class of women from the Air Force, Coast Guard, military, and naval academies. Her recruiter (played by Harry Dean Stanton) sells her a life of luxury and beaches, emphasizing that the military will cater to her needs, a concept she synthesizes through the lens of never having to be independent. In the military, as in life, there aren’t any concessions made for Judy. Once again, a man has told her what to do and she’s bought it, but with no exit strategy, she can’t do anything but endure.

Private Benjamin never tries to say the military isn’t for women. As Benjamin becomes more confident, she dreams of being a Thornbird, an elite squad of parachute jumpers. Because of the strides in second-wave feminism, there’s never any doubt Judy will get the position she wants; if anything, it is the male ego that stands in her way. After Judy becomes a Thornbird she’s sexually harassed and almost assaulted by her commanding officer, a harbinger of how the decade would be dominated by a new code of conduct regarding harassment in the workplace. Though Judy decides to leave, it’s never a moment of weakness, but humiliation for her C.O.

Because women were now in the workplace, establishing their own identities, it’s not surprising that Private Benjamin makes Judy a woman who understands how past history has limited women. Case in point: Her relationship with Yale is absent any sexual satisfaction. Unlike later films in the ‘80s, where the goal is to remind women they can’t “have it all” — success in both their business and personal lives — Private Benjamin allows for both.

After achieving her career goals, Judy falls in love with Henri Tremont (Armand Assante) a picture-perfect man who gives Judy the sexual gratification she’s been missing and, more importantly, a man she feels deserves her. But where she was willfully ignorant of her husband’s faults, she notices Henri is temperamental and a womanizer. Instead of trying to please him and go through with a marriage she knows she’ll be stuck in, she rejects Henri and ends the film independent and confident of her future. Private Benjamin takes the strides women made in the ‘70s and crafts a world where a woman can take on a man’s realm in business, find love, and get married or not — either is acceptable.

Goldie Hawn was the perfect star to play the spunky Judy. Her characters throughout the ‘70s were earthy and bordered on ditzy, yet possessed an awareness of how they hid their heads in the sand. Private Benjamin gave Hawn the tools to tell audiences she was more than just a cute blonde with a giggle. She was a serious actress who wanted to give women a role model to enter the ‘80s with. If only she’d been allowed to maintain that…

1987 was the apotheosis of the Backlash Era, with landmark films like Fatal Attraction and Baby Boom acting as reminders to women that nothing matters unless you have a happy relationship to go with it. Overboard takes that to extremes with the story of Hawn’s Joanna Stayton, a wealthy heiress who spends her days painting her nails, berating her staff, and ignoring her husband. After she falls off her yacht and contracts amnesia, a carpenter she’d insulted, Dean (Kurt Russell), gets revenge by telling her she’s his wife, taking her home, and expecting her to be caretaker to him and his three sons.

Where Judy Benjamin pulls herself up by her bootstraps, Joanna Stayton is an entitled daughter of privilege. Though she’s independently able to take care of herself — it’s actually her buffoonish husband, Grant, who needs her financially — her shrewish personality is her ultimate sin. It is only through Dean knocking her off her pedestal, demeaning and humiliating her in his ramshackle house, that she learns what’s important in life. Private Benjamin brings up questions of sexual harassment in the workplace, yet by 1987 the audience isn’t meant to bat an eye at Dean making jokes about Joanna’s presumed sex life with him. Later on, when their relationship turns romantic, there’s no issue regarding where the boundaries are, considering Dean has kidnapped and lied to Joanna.

Overboard’s entire conceit is that women are the only ones who can take care of a household. Dean’s house is slovenly, his children illiterate, and he has no issue with that; he reminds Joanna that he and his boys are “pals.” This puts it on Joanna, in her new position as matriarch of the household, to fix everything. She not only becomes proficient at homemaking, she has time to come up with an idea for the golf course that Dean and a friend want to create. (The film makes no mention of the fact Dean and his friend profit from Joanna’s idea, becoming the faces of this thriving golf course.) The script presumes that the household realm is entirely a female’s domain. Any woman could have come in and fixed it, so long as she’s a woman. Where Private Benjamin told women they had the tools to care for themselves, Overboard demands they care for others, even if they’re not biologically yours.

The end of the film also posits a world where a woman is forgiving. Where films like Fatal Attraction require the death of the overly ambitious female, Overboard compels Joanna to forgive Dean for his flaws because they have true love between them. Her money can be utilized to benefit Dean and his boys, making them upwardly mobile. The difference between him and Grant, Joanna’s soon-to-be-ex, is that Dean puts Joanna in her place. She won’t get a big ego under his watch because he’s shown her reality. This is brought to its inevitable conclusion when Dean asks what he can offer Joanna that she doesn’t already have. She tells him, “A little girl.” In the end, Joanna learns independence and wealth are disposable and can’t stand in for domesticity, where a woman has a husband and children to care for.

Hawn’s appeal to both men and women allowed her to transition and represent women at each end of the decade. Her Judy Benjamin is fierce yet soft. Her Joanna Stayton is cold but pliable. Goldie Hawn came to embody the ideal woman, and remind women in the audience what they could do to be happier people.

Join our mailing list! Follow on Twitter! Like us on Facebook!