When Tobe Hooper inked a three-picture deal with the Cannon Group in 1983, he was basking in the glow of Poltergeist’s success, even if that glow was dimmed somewhat by the persistent rumors that he was not the dominant creative voice on the set. Regardless, producer Menahem Golan hand-picked Hooper to film Colin Wilson’s cult science fiction novel The Space Vampires, giving him the largest budget he ever enjoyed ($25 million), a generous shooting schedule (120 days), and access to the finest technicians and some of the largest soundstages in the UK. Too bad Hooper’s deal didn’t include final cut, as he learned when the 116-minute version he delivered to Cannon and TriStar Pictures was shortened by 15 minutes for its U.S. release, and retitled Lifeforce. These were far from the only bumps it encountered on the way to the screen.

The trouble with Lifeforce began with the script, which Hooper admits on the 2013 Scream Factory release (upgraded to 4K last year) was still being written while cameras were rolling. Of the two credited screenwriters, Dan O’Bannon was hired because he had worked on Return of the Living Dead while Hooper was attached to direct it. (When Hooper jumped ship to Cannon, O’Bannon replaced him in the director’s chair.) Along with his writing partner Don Jakoby, O’Bannon took on the task of translating Wilson’s cerebral novel, which has deep discussions about all kinds of vampirism, into cinematic terms. They also transposed its story, set in the far-off future of 2076, to the present day. Not only did this avert production headaches – $25 million was a lot of money, but it would only stretch so far – it also allowed the film to incorporate Hooper’s idea of tying in Halley’s Comet, which was set to return the year after its release.

While they invented a more apocalyptic finale than the one in the novel, O’Bannon and Jakoby kept the opening mostly intact, changing the spaceship Hermes to the Space Shuttle Churchill and having it discover an alien craft in the coma of Halley’s Comet rather than an asteroid field. Once the crew decides to bring back three of its occupants (found in suspended animation), the film diverges wildly from the book. Instead of being branded a hero, as the commander of the Hermes is, the Churchill’s Col. Carlsen disappears for an entire reel while his ship is found approaching Earth with no one at the controls and three unidentified humanoids in the hold. When the Churchill’s escape pod is found with Carlsen alive inside, he describes what happened during the return trip – a sequence reminiscent of the log of the captain of the Demeter, to which Bram Stoker devotes a chapter of Dracula – but by that time all hell has already broken loose at London’s Space Research Centre (along with one of the aliens, which are revealed to be energy vampires).

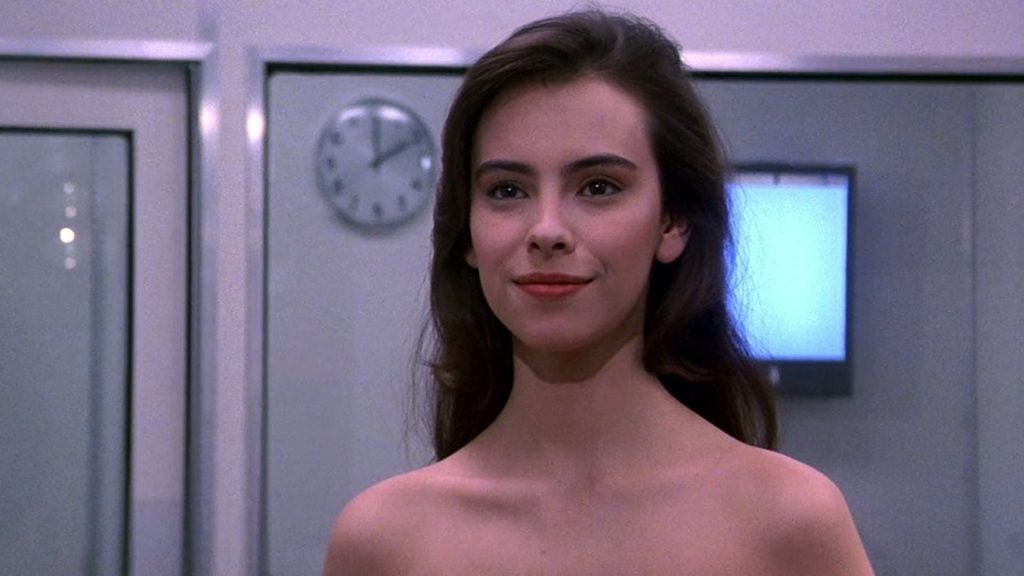

Few would deny that the main reason for Lifeforce’s cult (outside of Tobe Hooper completists) is the performance of Mathilda May as the Space Girl, who spends the majority of her screen time unclothed. (Unsurprisingly, Hooper had great difficulty casting the role.) As such, May tends to overshadow the contributions of some of the other actors, but the ensemble – led by Steve Railsback as the haunted Col. Carlsen – is top-notch, treating the material with the utmost seriousness and not allowing it to tip over into camp. And while her male counterparts don’t get as much of an opportunity to strut their stuff before being blown to bits, their physiques are similarly impressive.

Also impressive are the special visual effects, supervised by Academy Award winner John Dykstra, although many of the shots of the interior of the alien ship were trimmed down in the theatrical version to get through the first act that much faster. (Fully half of the cuts are in the first 34 minutes.) Likewise lost in the shuffle was much of Henry Mancini’s score, such that he shares his title screen with Michael Kamen and James Guthrie, who are credited with additional music. Cannon and TriStar’s alterations did little to enhance Lifeforce’s commercial prospects, however, and in a summer crowded with would-be blockbusters, it crashed and burned, grossing less than half its budget.

In spite of Lifeforce’s failure at the box office, a three-picture deal with Cannon was a three-picture deal, so Hooper got to do his effects-heavy remake of Invaders from Mars (again scripted by O’Bannon and Jakoby, with visual effects by Dykstra) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2, which returned him to his down-and-dirty roots. Jakoby, meanwhile, was drafted to write Cannon’s notorious Death Wish 3, and eventually penned the screenplay for John Carpenter’s Vampires, which shares many thematic elements with Lifeforce. Just no naked space vampires.

“Lifeforce” is available to stream, rent, or purchase on a variety of outlets.