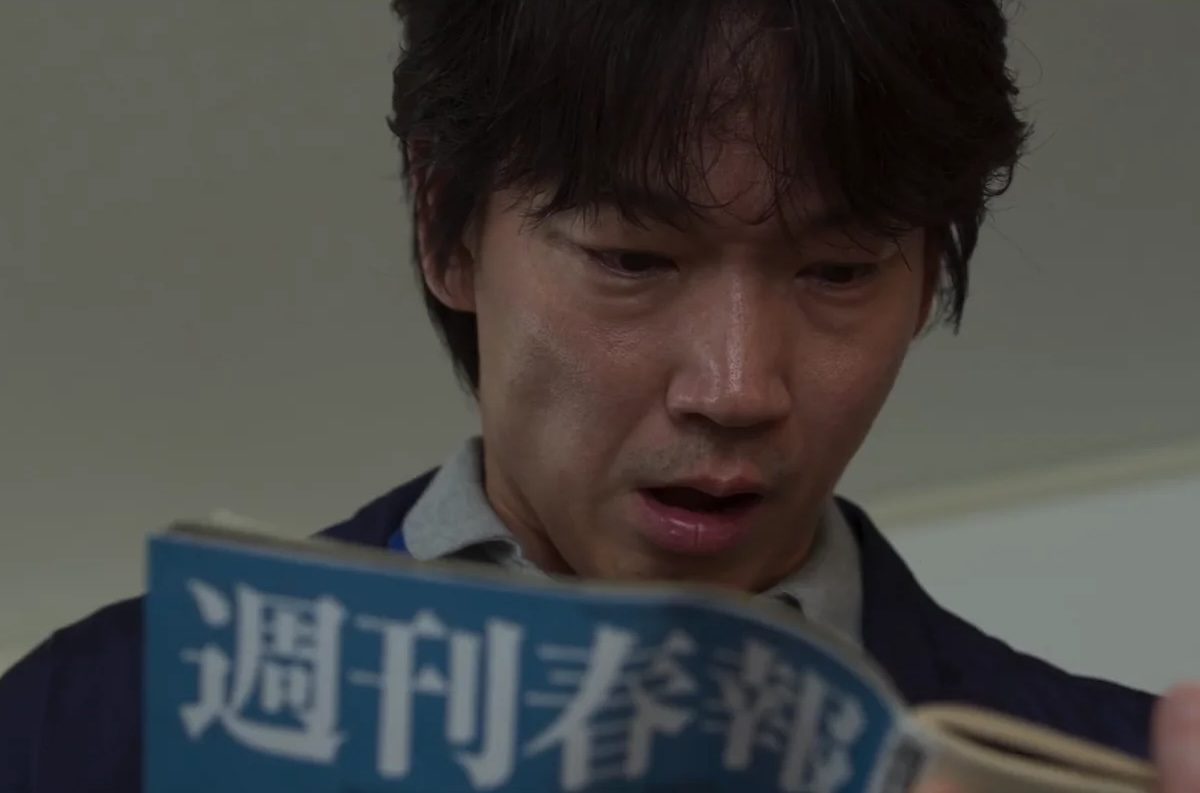

Here is (I think) a high compliment: I completely forgot that Takashi Miike directed Sham. The famously prolific and provocative Japanese auteur’s credit was how the picture made it onto my Tribeca schedule to begin with, but I made it weeks ago, and have slept since then, so I forgot everything about it as it uncoiled in front of me. (I highly recommend this general blind-watch experience whenever possible.) And it’s not that Miike is a one-trick pony—far from it, in fact, after previously stretching beyond the genre films for which he’s best known. But this is a based-on-a-true-story courtroom drama, its own ball of wax, and he helms it with emotional sensitivity, formal discipline, and a fair amount of slow-boiling anger.

It begins as the story of a monster, an elementary school teacher who is cruel and violent, bullying a student whom he’s singled out for special harassment because of the boy’s “tainted blood” (his mother tells him that his grandfather was American). Miike summons up all of our sympathy for this boy and his protective mother—and then turns it, revealing, through the teacher’s testimony in the eventual trial, that their claim “contains no truth whatsoever,” and detailing how a fib can become a scandal. Only then does it become a courtroom drama, and a good one, with secrets uncovered and motivations revealed and such. Miike’s fierce intelligence keeps it from falling into formula, however, and his cast (including Kazuya Kamenashi, Ko Shibasaki, and Audition alum Ken Mitsuishi) are all first-rate.

One of the many reasons cringe comedy is so hard to pull off is because it’s so dependent on the specific charisma and alchemy of the protagonist. Larry David, for example, can get away with being a rude narcissist because he’s funny about it; we end up granting Michael Scott a fair amount of leeway because of his undeniable vulnerability. The insurmountable problem with writer/director Charlotte Ercoli’s Fior Di Latte is that its main character, lovelorn playwright Mark (played with maximum irritability by irritability specialist Tim Heidecker) is so endlessly off-putting, odd and gross and obnoxious and unlikable, a total drip who you just want her to cut away from. She does not.

Without a rooting interest of any kind, or any force of momentum in its place, Fior just lurches from scene to scene, smashing our antihero into whomever he thinks can help him reconnect with the pretty Italian girl (Marta Pozzan, giving it her all) who moved to New York City to make a go of it after his idyllic vacation in Italy, only to immediately (and understandably) regret it. Some of the supporting players mine laughs or pathos out of their underwritten roles; Kevin Kline, Julia Fox, and Gina Gershon all brighten things up, at least briefly, with their inherent charm. But they can only do so much.

Tribeca has always been a reliable source of documentaries about movies; my very first fest, clear back in 2009 (!), featured Blank City, the rather life-changing doc on the downtown New York movies of the 1980s, and recent slates have included such gems as Made in England: The Films of Powell & Pressburger and Enter the Clones of Bruce. This year’s must-see movie-about-movies is The Degenerate: The Life and Films of Andy Milligan, in which co-directors Josh Johnson (Rewind This!) and Grayson Tyler Johnson profile the no-budget filmmaker renowned among cult movie fanatics for his chaotic handheld camerawork, claustrophobic framing, over-the-top acting, and copious gore.

Most of Milligan’s movies aren’t good, in any traditional sense, but they’re also fascinating, and the value of The Degenerate is its desire to understand why—to probe his recurring themes, preoccupations, and obsessions, as well as providing valuable background into the avant garde theater and exploitation cinema scenes in which he was so deeply entrenched. Masterfully edited and surprisingly soulful, this is a must-see for a certain kind of film fanatic. You know who you are.

There have been enough restaurant scene (and, therefore, food porn) documentaries over the past few years that you would be forgiven for assuming Raoul’s, A New York Story is just another one—spotlighting, as it does, the French bistro that’s been a Soho cornerstone for half a century now. But its original owner, Serge Raoul, became a restauranteur by accident; started out as a filmmaker, as did his son Karim, who co-directs the film (and is also the current owner and operator).

So there are genuine ambitions at work here, and the sections about their respective moviemaking ventures are a welcome departure from the food-doc playbook. That goes double for the “New York story” elements of the title, as the bistro’s rise and shifts mirrored the city’s in many striking ways, up to and including the picture’s thoughtful meditations of the trap of tradition (and how it breeds conservatism). The free-floating, freewheeling structure could’ve made Raoul’s scattershot or overstuffed, but it feels personal and heartfelt instead.

But the best documentary I saw at Tribeca this year was apparently a popular favorite as well. Suzannah Herbert’s Natchez won the award for best documentary feature, as well as special jury mentions for cinematography and editing, and all are richly deserved. Herbert’s picture is a profile of the small town (1400 residents) of Natchez, Mississippi, and it explores the tension between history and nostalgia; this is a Southern Antebellum city, which is also being asked to reckon with the legacy of the slaves upon whose backs it was built.

The lead time of any movie, especially a documentary, means that rapid-responses aren’t exactly the norm, but it’s hard to imagine a film that speaks more directly and effectively to America under Trump 2.0 — everyone smiles and gets along and nods sadly and sagely, and does their best to say and do the right thing on camera (“Let me say this right,” one tour guide says, before stopping himself again and shrugging “I’m gonna get in trouble here”), but when there aren’t any judging eyes watching, certain folks will still go full racist. This would be a fine film under any circumstances, but right now, it feels particularly pointed and necessary.