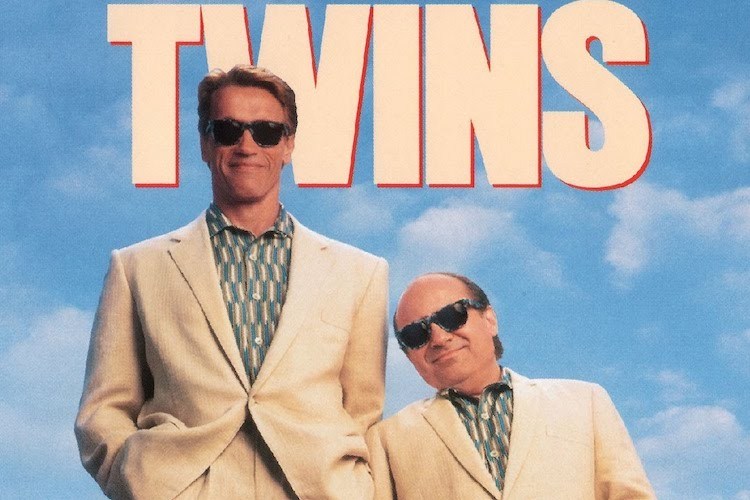

According to Hollywood lore and its IMDb trivia page, Twins was dreamt up during a desperate bathroom break by two writers whose only prepared pitch had just been shot down. I can’t find a credible source for that, but do I really need one? Have you seen Twins? Have you seen the poster for Twins? It deserves the blink-or-you’ll-miss-it jokehood of the fake posters from the video store that gets plowed by a bus at the end of The Lost World. Tom Hanks in Tsunami Sunrise. Robin Williams in Jack and the Beanstalks. Danny DeVito and Arnold Schwarzenegger in Twins.

That Twins is anything more than a fictional three-day rental from Blockbuster only makes sense as the flop-sweaty byproduct of accidental genius, birthed in a nameless executive’s washroom and inspired by the gun-to-the-head threat of unemployment.

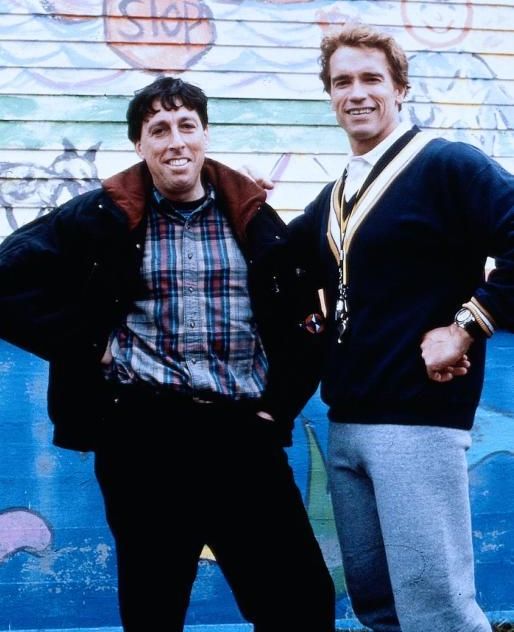

That Twins makes any sense as an actual movie is due in no small part to Ivan Reitman.

Of the holy trinity of comedy filmmakers spawned by National Lampoon’s Animal House — its director John Landis, writer Harold Ramis, and producer Ivan Reitman — Reitman is the most inscrutable. Landis is loud and raucous, a devotee of the Marx Brothers; Ramis was a Zen master whose Groundhog Day is regularly cited as an agnostic ode to religion.

What about Reitman?

Even though he’d already directed some Z-grade Canadian horror and earned his producing stripes on early Cronenberg films, Ivan Reitman was not the name everybody was squinting for in the Animal House credits, even though it was his baby. He desperately wanted to direct it, but Landis had more clout behind the camera. Reitman knew he was in the right time and the right place. It was the same gilded instinct that made him sit up and notice the shaggy improv show he caught in Toronto years earlier, The National Lampoon Show, with ready-to-pop players like John Belushi, Gilda Radner, and some other guy’s brother named Bill Murray. Reitman knew he was still on the bleeding edge of a new age in comedy, but he was starting to slip. So the summer after Animal House, he directed Meatballs, a bog-standard camp comedy salvaged by a Ramis rewrite and a Hail-Mary starring debut from Bill Murray, still young enough to be known as “The New Guy From SNL” but still Bill Murray enough to only let everyone know he was on-board by showing up the first day of shooting.

Five years later, Reitman direct the highest-grossing comedy of all time.

Ivan Reitman’s filmography speaks for itself. Ghostbusters. Kindergarten Cop. Stripes. Junior. Dave. And, of course, Twins. Yet it doesn’t inspire the same deep-dive explorations as his contemporaries’ work. He doesn’t have an immediately identifiable stock-in-trade style, like Landis. There’s no philosophical stream that gently carries all his movies in the same direction, like Ramis. Even as a character in the Second City/National Lampoon boom of the late 1970s, he’s a squarer peg than the rest. According to Chris Nashawaty’s essential account, Caddyshack: The Making of a Hollywood Cinderella Story, when Reitman showed up for the first rehearsal of The National Lampoon Show and started peeling off his winter wear, Bill Murray put it back on him piece-by-piece and steered him out the door again. Besides a few familiar faces like Murray along the way, it’s tough to nail down what makes an Ivan Reitman movie an Ivan Reitman movie.

But the first five minutes of Twins does an admirable job explaining it as it explains how Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito could come from the same human mother. A genetic experiment, of course. Borrowing the best bits and pieces of Top Men and creating the perfect child. But nobody counted on the leftovers making a child of their own.

That’s it. A few minutes of part-prologue, part-fairy tale and we’re off to the races. Grown-up Arnold decides to find his brother. Grown-up DeVito cheats on his girlfriend with his neighbor’s wife. The comfortable rhythm of 1980s comedy — montages set to songs found nowhere beyond the soundtrack, a scene in a bar lit only with neon and cigarette smoke, a superfluous crime subplot that turns the third act into an action movie — takes over. The toughest pill has already been swallowed. The late-game revelation that the twins have Force-grade telepathy strong enough for them to track each other hardly even registers.

“I called it my domino theory of reality,” said Reitman in a Ghostbusters retrospective for Vanity Fair. “If we could just play this thing realistically from the beginning, we’d believe that the Marshmallow Man could exist by the end of the film.” There is nothing so overtly unbelievable as 100-foot junk food in Twins, but the approach is no different. Ghostbusters opens with a haunting. Books float. The Dewey Decimal System is ruined. We never see what scares that poor librarian, but before we can wonder too hard, Bill Murray smarms his way across the screen and grounds us in welcome familiarity. It’s easy to forget because it’s such a cornerstone of 1980s pop culture, but Ghostbusters, simply put, is absurd.

On the screen, Twins takes fewer dominoes to believe. Off screen, it took a multi-million-dollar gamble for anyone to even consider it. In 1988, Arnold Schwarzenegger was not a funny man, at least as far as studios were concerned. If he wasn’t holding a gun or David Patrick Kelly off a cliff, nobody wanted to see him, or so The Powers That Be thought. So for his comedy debut, Arnold sought out the director of Ghostbusters, a movie some 19 spots higher than The Terminator on the biggest box office successes of 1984. Reitman was won over by his unexpected charisma and intelligence, neither of which had gotten much screen time by the late 1980s, and they made a very risky deal. Along with Danny DeVito, Reitman and Schwarzenegger wouldn’t take salaries on Twins in exchange for a sizable percentage of the profits. With a relatively low budget of around $16 million, the studio didn’t have much to lose. For their bravery, Arnold, Ivan and Danny earned record paychecks on a historic deal that no studio will ever agree to again.

Ivan Reitman made Arnold Schwarzenegger believable as a comedy star, but there were more challenges ahead of him.

Kindergarten Cop (1990) boldly plays Reitman’s style backwards. The Slightly Outlandish Prologue, in this case, is devoted to Action Arnold, complete with big guns and an ‘80s mall. The movie treats Comedy Arnold as the baseline, the grounding, even though it was only his second time top-lining a comedy. It’s all fish-out-of-water, but the confidence is wise and welcome. Comedy Arnold is fresher, friendlier, making the obligatory third-act action business more surprising and lending it unexpected weight. Fair credit goes to the casting. As far back as Stripes, which began its life as a doomed Cheech and Chong movie, Reitman mentions casting as one of his obsessions.

Junior (1994) sidesteps the whole Arnold-Schwarzenegger-Does-Not-Have-A-Womb problem by leaving most of the science to Emma Thompson. Nobody bothers explaining how that’d work because it isn’t important and can’t be explained (see also: how Ghostbusters 2 pretends all of New York City didn’t see 100-foot junk food wreck Manhattan). But make Emma Thompson, of Shakespearean import and British accent, a geneticist who seems to have no problem with such logic and the audience suddenly doesn’t mind it either.

Dave (1993) bets it all on the same principle. It’s not the number of dominoes, but the size. If you can buy that Kevin Kline is a presidential impersonator so good that he can successfully double for the president in front of the nation, you’re golden. Sigourney Weaver’s first lady sees through it before long, reminding us what we’ve fallen for, but by the end, you still believe that she’d fall for him, too. Actors like Kevin Costner and Warren Beatty were considered for the dual role, but they couldn’t have sold the wide-eyed warmth like Kline did. We believe it because we like him and we’re just as naïve to it all as he is. And he’s just as excited to see Schwarzenegger in a cameo as we are.

“For some reason, I get attracted to difficult premises,” said Reitman on the objectively bizarre set of Junior. “I mean, they’re somewhat gimmicky: Ghosts exist and you can zap them; Arnold and Danny are twins; a man who looks like the President takes over and does a better job. But I try as hard as I can to find a level of reality in the fantastic premises that I latch onto.” It’s a rare admission from a filmmaker who speaks more often as a producer than director. That’s likely why the same article references a well-publicized swipe at him a few paragraphs later: “He is a businessman, not an artist.”

It’s as unfair as it is incomplete. Any allegation that he’s “not an artist” comes from a superficial comparison to his contemporaries. Unlike Ramis and Landis, Reitman’s work does not easily lend itself to video essays. He probably won’t get a film school named after him. He doesn’t show up in as many books about Saturday Night Live, the National Lampoon or Second City to offer drug-addled anecdotes.

But what Reitman does better than any other comedy director is sell the unbelievable. For the child actors in Kindergarten Cop, he established the “Five Reitman Rules of Filmmaking: listen, act natural, know your character, don’t look in the camera, and discipline.” While obviously aimed at keeping 4-year-olds on task, those rules work as a primer on Reitman’s whole approach. If you can make it real, you can make it funny — but never, ever wink.

There’s more to explore in Reitman’s technique; he disguises improv better than any Apatow-acolyte working today, for instance. But for a crash-course in Reitman 101, try Twins, a comedy that’s now 30 years old, that shouldn’t be anything more than a background gag in another movie, but miraculously still is.