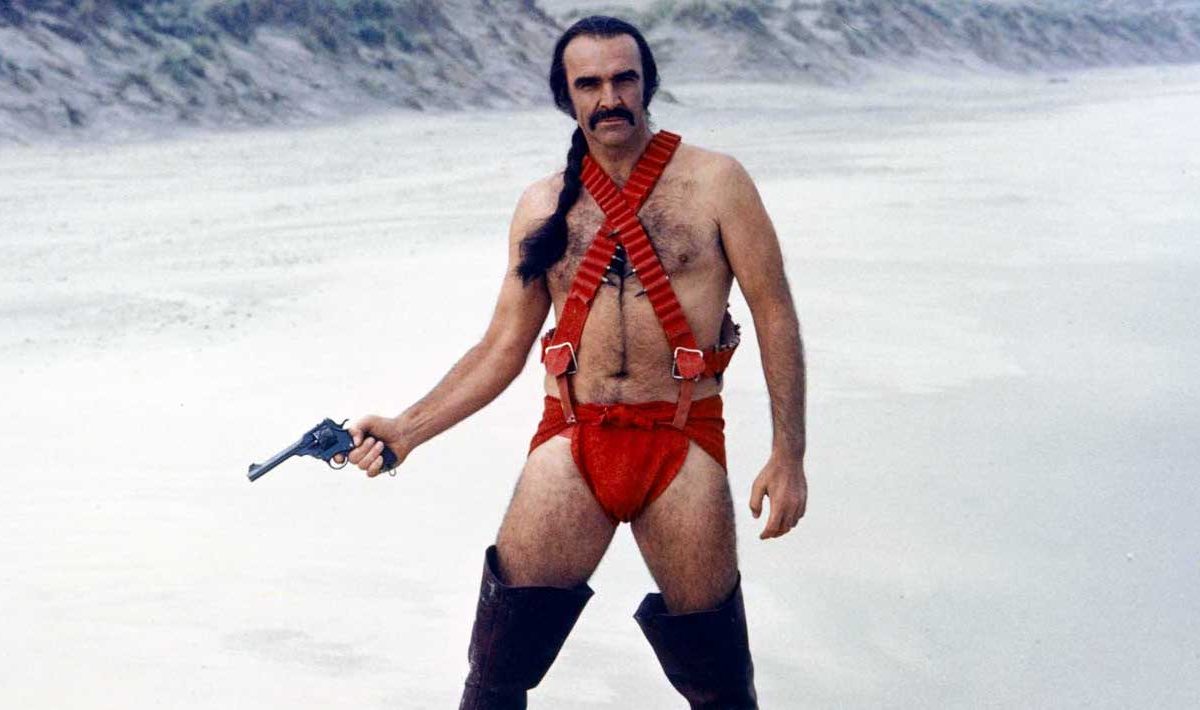

Look up never-ending listicles of the so-called worst movies of all-time and the chances are you’ll see Zardoz mentioned a few times. John Boorman’s genre-melding dystopian fantasy has become infamous as a brain-bending flop even among those who haven’t seen it (and, to be frank, that’s most people). Just the image of Sean Connery in bondage-esque red underpants with slutty thigh-highs has become an internet representation of an epic cinematic failure, up there with Tommy Wiseau’s pained cries and Dutch-angled John Travolta. Unlike many maligned hyper-ambitious follies of its era, from Sorcerer to The Long Goodbye, Zardoz has not been re-examined or reclaimed by critics as a cult hit or before-its-time entity. Much like another controversial Boorman flop, Exorcist II: The Heretic, it’s still seen as a straightforward bad film. Yet it seems limited to dismiss something so outwardly fascinating and high-level, both technically and narratively, as a mundane disappointment. On the eve of its fiftieth anniversary, Zardoz demands your respect.

Following the success of Deliverance, Boorman had planned to adapt The Lord of the Rings. After spending years working on a script that included a threeway kiss between Boromir, Aragorn and a teenage Arwen, sinister puppet shows, and a Sauron who looks like Mick Jagger, the funding fell through. Eager to use many of the Arthurian and New Age ideas he’d plundered for his Tolkien reimagining, Boorman managed to procure $1 million for his next project, even though nobody at 20th Century Fox had a clue what the film was about.

To give Zardoz the speediest of summaries, it depicts the future of 2293 where humanity is divided between the elite Eternals and low-class Brutals. The former live cloistered in a Vortex where they do not age but have grown bored with immortality, while the Brutals are murderous rapists either forced to grow food for their overlords or terrorize one another into servitude. One Brutal exterminator named Zed (Sean Connery) finds his way into the Eternals’ world via the talking stone head of Zardoz and works to find a way to destroy his oppressors. Sort of.

At the behest of the studio, Boorman added a preface to the movie where the basics of the plot are detailed, but it doesn’t demystify the grandeur or proud impenetrability of Zardoz. Indeed, Boorman wanted to create a mystery that both embraced the metaphysical while satirizing its own overblown splendor (contrary to popular belief, you are supposed to laugh at this movie.) Boorman’s ability (and troubles with) stretching a comparatively small budget to its limits gives Zardoz its unique look: part psychedelic rock band album cover, part medieval tapestry (echoed in the monastery-like score), part abandoned set painting from that unmade Lord of the Rings adaptation. For every moment that dazzles, there is one that feels like lo-fi British sci-fi straight out of early Doctor Who. Zed’s gaining of all of human knowledge is shot like a Bond movie opening, while the Eternals’ communication methods echo bad acting school exercises. The oft-derided Brutal costume is a parody of toxic masculinity, blatantly oversexed and crotch-centered. Connery, for his part, is committed to the macho dominance of this ridiculous man, bred to be a rapey savior to the Eternals. It’s the flipside to Bond: what if his sexuality really was a superpower?

Nudity is, of course, frequent but totally joyless as the Eternals have become both sterile and impotent over the centuries. The only way one can be punished in this system is to be forcibly aged and left to putter around an endless party of mentally unsound elderly prisoners, and even they seem to be having more fun than the ones in charge. All the Eternals seem to do is legislate over minor errors made across the centuries, “every little sin and misdemeanor raked over.”

This is a rare dystopian story in which the hellish future has been dictated not exclusively by political or scientific folly but by the arts. The carnage of the Brutals and their eventual worship of a giant head that spews guns is essentially the pet project of a bored artist with too much time on his hands. His influences are not technology but The Wizard of Oz, and his goals aren’t rooted in self-interest or progressiveness but pure apathy with his alternatives. The “perfection” of the Eternals has given way to nihilism, sexlessness, and total sensory starvation, so birthing an alternative defined by callousness that is inspired by bastardized readings of children’s stories is a damning inevitability.

Rather than help their fellow man, they have committed to exacerbating the scourge of the class divide, even though it has brought misery to both sides of the equation. They deliberately ignore the pain of the enslaved who provide for them, declaring, “You can’t equate their feelings with ours.” This utopian alternative to the basic tenets of human existence – love, sex, death – is empty, and all of the philosophizing it hoped to inspire is nothing but a dead end. When the giant head of Zardoz infamously proclaims, “The gun is good, the penis is evil,” you get his point. By the end, when the Brutals invade, the Eternals welcome with open arms the only experience they’ve yet to have, the one thing their former slaves can provide for them: death.

A lot of Zardoz is plodding and incoherent. Boorman would admit to being inebriated during much of its creation and that he’d cut out a lot in hindsight. He would bring more clarity to his fantastical aesthetic with the superior Excalibur, while the Wachowskis would make a lot of his ideas more accessible in The Matrix. Yet Zardoz as it stands is a unique endeavor, the kind of film that could only have existed in 1974, when this sort of ambitious and undiluted vanity project was conceivable under the studio system. Amid its muddle of ideas is a scathing message for the future: we are forever bound by sex, by art, and by violence, and whatever you do with that combination will make or doom us. In Boorman’s eyes, the latter seems inevitable. “Is God in show business?” asks Zardoz. Well, that or he has an especially sick sense of humor.

“Zardoz” is available for digital rental or purchase.