When it was announced that Quentin Tarantino’s next film would involve the Manson Family murders, the news was met with excitement, outrage, trepidation, and — most curiously — surprise.

First of all, you would think that after a quarter-century of following his singular career, people would stop trying to anticipate a filmmaker as idiosyncratic and obsessive as Tarantino. But also, we are in a cultural moment where the intersection of crime and cinema during the violent, paranoid decade that followed the turbulent but idealistic ‘60s is seeing a surge of interest.

The murders of seven people (including actress Sharon Tate, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant) committed by four of Manson’s followers in August 1969 would symbolically mark the end of the free love revolution and usher in a “hangover decade,” the first half of which saw a dramatic increase in crime, vast turmoil over the war in Vietnam, and the Watergate scandal that led to the resignation of President Nixon. The second part of the decade didn’t fare much better, thanks to recession, rising inflation, and a prolonged energy shortage, all of which combined to create an overwhelming sense of national malaise.

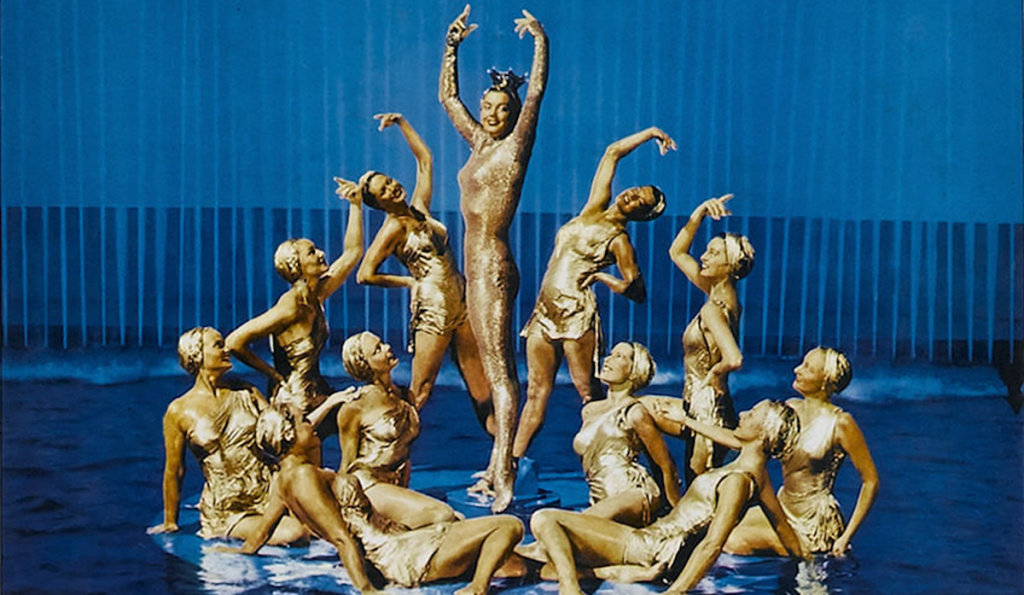

Yet for as bad as things were in reality, this was the most creatively fertile period for American movies since the Golden Age of the 1930s. Freed from the constraints of the crumbling studio system and emboldened by the new cultural permissiveness, this would come to be known as the era of New Hollywood. Surprise hits Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Graduate (1967) opened the doors before Easy Rider (1969) — released only a month before the Manson Family took up their killing spree — blew them off the hinges. A new form of auteur-driven cinema reigned for the better part of the decade, until a few high-profile bombs (most importantly 1980’s Heaven’s Gate) and the unprecedented success of a new kind of blockbuster (as personified by Jaws [1975] and Star Wars [1977]) led the studios to adopt a new corporate mindset where mass appeal and opening weekend box office took precedent over all other considerations.

While Charles Manson himself deserves no credit for the creative renaissance of this period, the impact that his crimes had on the creative class cannot be overlooked. The stories told in the films of the day were darker, more violent, and often deeply cynical (if not downright nihilistic). Sex and death mingled in ways that seemed inseparable from the goings-on of Manson’s murderous free-love cult, as does the mixture of existential dread and ennui that reverberates just under their surfaces.

This is to say nothing of the personal fear, anger, and, yes, even excitement, that many in the Hollywood community felt as a result of the crimes. Sharon Tate, along with husband Roman Polanski, often played host to the who’s-who of the up-and-coming New Hollywood crowd at their home in the Hollywood Hills. In the wake of the massacre, it became a popular refrain amongst this set to claim that you’d been invited to that house on that very night but hadn’t gone. Beyond even the victims, many in that same social circle also had some connection to Manson himself.

Karina Longworth weaves together, in great detail, the vast network that joined Manson to the Hollywood in-crowd in the 2015 season of her podcast You Must Remember This (which, in her own words, “explores the secret and/or forgotten history of Hollywood’s first century”). She does this by digging into the personal history of not only Manson, but also his followers, his victims, and those who found themselves linked to him. This includes well-known acquaintances such as Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys and record producer Terry Melcher, as well as more obscure connections such as Doris Day, Kenneth Anger, Dennis Hopper, Daria Halprin, Michelangelo Antonioni, and a myriad of others.

Thanks to YMRT’s fortuitous timing (its Manson series came out in the midst of a true-crime boom that included Serial, Making a Murderer, The Jinx, and the coming wave of O.J. Simpson nostalgia), as well as Longworth’s superb gifts as a storyteller, the Manson Family murders have been reframed in such a way that they now seems inseparable from the community which they upended.

Though not much is known about Tarantino’s upcoming film beyond a few early casting rumors, there are indications he will take an approach similar to Longworth’s (though considering Tarantino’s demonstrated willingness to alter history, what the end result looks like is anyone’s guess at this point).

During the 2016 Lumière Festival in Lyon, France, Tarantino held a masterclass on the subject of New Hollywood, in which he revealed that he had been conducting research for the past four years on that epoch, with a particular focus on the year 1970. He said:

New Hollywood was the Hollywood and anything that even smacked of Old Hollywood was dead on arrival. The more I started going to the library and looking up newspaper articles of what it was like, I realized New Hollywood had won the revolution but whether it would survive wasn’t clear. Cinema had changed so drastically that Hollywood had alienated the family audience. … Society demanded (the Hollywood new wave) but that doesn’t mean that they supported it as a business model and it made me realize that New Hollywood cinema from 1970-76 at the very least was actually more fragile than I thought it was. The experiment could have died in 1970.

At the time, Tarantino teased a forthcoming project based on his research. It now seems likely that his mystery 1970 project is one and the same as his Manson script, or, at the very least, a companion piece to it, and it wouldn’t strain credulity to presume that the film will likely focus not only on the police investigation into the Tate-LaBianca murders, but also the larger social scene in which they occurred, as well as the culture of film that both preceded them and evolved within their shadow.

Tarantino differs from many other chroniclers of this period in that his scope extends beyond just the films that came from the “movie brats” of the American New Wave. In his masterclass, Tarantino cited everything from Italian giallos to American Blaxploitation. This is fitting, considering that one area of ’70s film where the Manson influence can be most heavily felt is the grindhouse, both in violent genre classics such as Last House on the Left (1972) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and in the numerous exploitation titles that openly sought cash in on the story while it was still in the headlines, including The Helter Skelter Murders (aka The Other Side of Madness, 1971) and The Manson Massacre (aka The Cult, also 1971).

Tarantino isn’t alone in his fascination with this period of Hollywood history. James Franco has a directorial effort in the can with an immediately recognizable link: Zeroville, an adaptation of Steve Erickson’s phantasmagorical 2007 novel, which follows an autistic Los Angeles transplant nicknamed Vikar (played by Franco), obsessed with movies and prone to violence, as he bears witness to the rise and fall of New Hollywood. The story plays out like a spooky, more dreamlike, gnostic version of Forrest Gump, complete with appearances from several major figures of the era (sometimes thinly veiled, sometimes not).

The novel begins with Vikar being arrested on suspicion of murder after he’s found camping out in the Hollywood Hills at the exact time of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Though he is soon released, unease and suspicion follow him throughout the first quarter of the novel, with several members of the Hollywood film community that he has fallen in with remaining convinced that he was a member of the Manson cult. At one point, he notices a pre-fame Robert DeNiro studying him during a party at the famous beachfront house of future Taxi Driver producers Michael and Julia Phillips. The reader quickly puts two and two together and realizes that, in the world of the novel, the character of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver is based on Vikar by way of Charles Manson.

Despite being completed in 2015, the film has remained indefinitely shelved, with no release date in sight (an early teaser trailer was released online, only to be pulled and scrubbed shortly thereafter). Hopefully the movie sees a release within the next year, because regardless of quality, and whether or not the above-mentioned scene ends up in it, it will help to highlight the connective tissue between all of these various narratives.

As to the question of “why now?” in regards to said narratives, it would be tempting to point to the current political climate, were it not for the fact that all of these projects were either completed or well into development by the time the current-day upheavals fully cemented themselves. This is not to say, however, that there hasn’t been something in the air these past few years that makes us look back to our recent history and see something resembling our current predicament there.

Megan Abbott — co-author of the newly published comic book series Normandy Gold, a political noir set in ‘70s D.C. and imbued with a heavy dose of the same existential dread that runs through Alan Pakula’s celebrated “Paranoia Trilogy” (Klute, The Parallax View, and All the President’s Men) — posited just such a possibility when I asked her about it. “It’s hard not to speculate that we all felt something coming, some sense of things falling apart, narratives losing their meaning, a distrust in structures of authority,” she said.

This idea is doubly interesting when considering structures of authority beyond those of our national politics. For New Hollywood to have risen in the first place, it was essential for the old guard to collapse, a fate it helped bring down upon itself by investing obscene amounts of money into giant spectacles that failed to connect with audiences. While the comparisons are by no means 1:1, it’s hard not to look at the rate of diminishing returns for the current glut of unwanted tent poles and not draw parallels to the fiascos of Cleopatra (1963) and Dr. Doolittle (1967).

Even should the current state of Hollywood prove itself a bubble and end up bursting, it seems improbable that anything resembling New Hollywood would rise to take its place. However, that’s not to say that the coming generation of filmmakers, armed with more access to technology and equipment than ever before, and with myriad new distribution platforms at their disposal, won’t tap into the current miasma of anger, paranoia, and doom, and fill the vacuum with darker, more complex stories once again.

One possible cosmic sign that points to just such a possibility is Charles Manson’s return to the headlines over the course of the last year. Probably no one deserves to suffer the indignity of having someone trick them into falling in love just so as to steal their bones (someone make this movie soon, please and thank you), or to have their encroaching death casually objectified (though if anyone does it’s old Charley), but it would certainly be fitting — at least in a narrative sense — for him to shuffle off this mortal coil during a period of upheaval so similar to the one in which he first entered the public consciousness, and for the movies to once again follow his lead. Perhaps the man is a true prophet of Armageddon after all.

Zach Vasquez lives in Los Angeles but has an alibi for the night in question.