The first cut comes a few minutes into the second scene of Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker, and it happens so quickly that if you glance away for a second, you might not catch it. Sol Nazerman (Rod Steiger) is relaxing in the backyard of his sister’s place, and she offhandedly mentions, apropos of nothing, “Twenty-five years next Thursday,” and there’s a flash, no more than a flash, of another woman’s face. We saw her in the first scene, a wordless sequence of a day in the country where the visions of pastoral bliss are so over the top – slo-mo frolics through meadows, drawing water from a scenic lake, comforting and idyllic music – that you feel like they must be a fake-out. And they are.

Something terrible happens (we’ll find out exactly what later), and then Lumet cuts to the tract houses of suburban New York, where the contrasting vulgarity – loud radio, braying relatives, obnoxious teenagers – is striking. And Sol’s sister-in-law is going on about one thing or another, and then she mentions that anniversary, and there’s that cut, and then immediately back. “My poor sister Ruth,” she says.

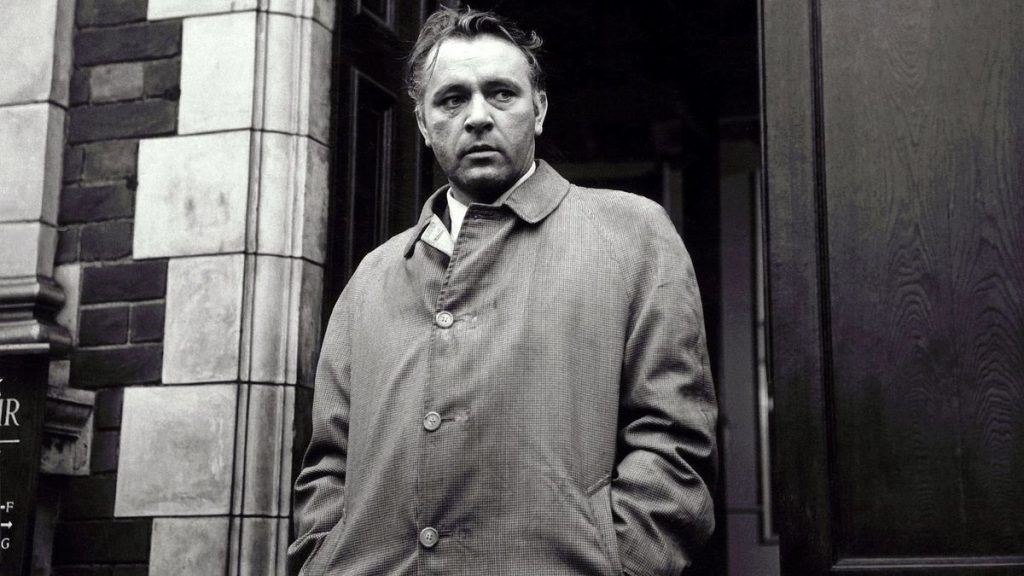

The editor is Ralph Rosenblum, and that innovative editing technique is one of The Pawnbroker’s primary claims to fame; in his memoir Making Movies, Lumet writes, “Within a year after the picture opened, every commercial on television seemed to be using the technique. They called it ‘subliminal’ cutting. My apologies to everyone.” The film is also remembered for Rod Steiger’s staggering, Oscar-nominated performance, and as one of the definitive New York movies of the 1960s, shot in the period just before such location shooting became (after years of struggle) commonplace.

Lumet was one of the great New York directors – born in Philly but raised on the Lower East Side, he helmed such quintessential Gotham pictures as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, and Prince of the City. And, like all those movies, The Pawnbroker looks, sounds, and feels like The City. Sol Nazerman’s pawnshop is in Harlem, just off Park Avenue and 116th Street, an ideal location to explore the friction between the Jewish and African-American communities.

Strictly speaking, his job is customer service, but there’s not much of it to speak of; he interacts with others in a flat, matter-of-fact manner, often just barking the dollar amount he’s offering, steadfastly refusing to engage in small talk or pleasantries, or to acknowledge the desperation that has brought most of them to his counter (junkies needing cash for a fix, a gaunt but pregnant woman trying to pawn her wedding ring). On the other hand, when his customers go off on him (that wild-eyed junkie, for example, calls him a “money-grubbing kike”) he seems nonplussed. There’s no getting to Sol Nazerman.

Marilyn Birchfeld (Geraldine Fitzgerald) finds this out the hard way. New to the neighborhood, she enters his shop soliciting donations for a neighborhood youth center, but also, it seems, desperate to make a human connection with him. He rebuffs her, cruelly and condescendingly. “Do you always think the worst of everyone?” she asks, and it’s a reasonable question. But the more we find out about Sol, the harder it is to blame him for it.

At the end of that opening tableaux, Sol and his family were captured by Nazis and taken to the concentration camps; only he survived. This repressed, tortured soul suffers from what we now define as PTSD – the fences of the neighborhood remind him of the concentration camps, a ride on the subway of the cattle car there, and so on. Rosenblum’s “subliminal edits” dramatize these connections, on the screen as they exist in Sol’s mind’s eye, to such devastating effect that it’s frankly horrifying the editing style became nothing more than a gimmick for flashy filmmakers and Mad men, because Rosenbum and Lumet aren’t using it as a flourish. They’re deploying and sculpting the visual language of cinema to replicate thought and memory, the specific way seemingly innocuous images can trigger similar, painful ones from our past.

With such potent memories so easily triggered, it’s somewhat surprising that he lives and works surrounded by bars and barriers – a literal cage in the pawnshop separates him from the customers, and cinematographer Boris Kaufman often places those bars between Steiger and his camera, or lights them to cast shadows across the actor’s face, to underscore the degree to which Sol is trapped by his circumstances. Or is he? At first, it seems, the pawnbroker is trapped, as he was in the war. But as the story progresses, it becomes clear that he’s put himself there, closing himself off; the cage is the buffer he uses to separate himself from the world.

“The Pawnbroker was about how and why we establish our own prisons,” Lumet wrote – and it’s also about how we break free of them. As Sol’s ability to repress his pain and suffering crumbles, Lumet and Kaufman stage a beautiful (and, at that time, unusual) montage of Sol walking the streets of New York City. As a snapshot of the mid-‘60s city – capturing, in particular, the marquees of Times Square and the brand-new Lincoln Center – it’s invaluable, but there’s more to it. Sol is trying to clear his head, and come to terms with both his past and his present, and get to a place where he can grapple with his memories. He goes, then, to Marilyn, the only person who has reached out to him; he admires her apartment, and the little terrace with the view of the river. It’s only when he walks out into that (comparatively) fresh air and open space that he can speak freely. Out in the open, he can finally open up.

It doesn’t last, of course; no sooner has he tentatively opened this door than he slams it shut, and everything goes sideways. Nothing is ever that simple, and these things often don’t take right away. But the closing images of this powerful film – his silent howl of pain and regret, the blood literally on his hands, a stigmata metaphor that isn’t subtle but sure is effective – make it clear that Sol Nazerman has changed, and has seen the damage he is doing to himself, and to those around him. To take that journey with him, in this masterful but difficult film, is an act of emotional and mental exhaustion. But it’s necessary. The best films, as has so often been said, put us in a character’s shoes for two hours. The Pawnbroker does more than that – it puts us in his head.

“The Pawnbroker” is now streaming on Amazon Prime.