Tom Ripley is a chameleon. The character introduced by author Patricia Highsmith in her 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley is especially adept at shifting his personality and appearance to appease the particular people he’s interacting with, in order to extract whatever he needs from them. So it’s fitting that Ripley has been portrayed in film by five strikingly different actors, in five films that take remarkably different approaches to telling his story. There’s every reason to believe that the upcoming Netflix series Ripley, from creator Steven Zaillian, will offer another entirely new angle on this malleable character.

Even so, there’s a core to Ripley that is captured in each screen adaptation, beginning with French director René Clément’s 1960 film Purple Noon, which was made before Highsmith had written any further Ripley novels. As played by international sex symbol Alain Delon, Purple Noon’s Ripley is suave and magnetic, making his jealousy and competition with the wealthy Philippe Greenleaf (Maurice Ronet) into a more balanced rivalry, both treating each other with some amount of cruel manipulation.

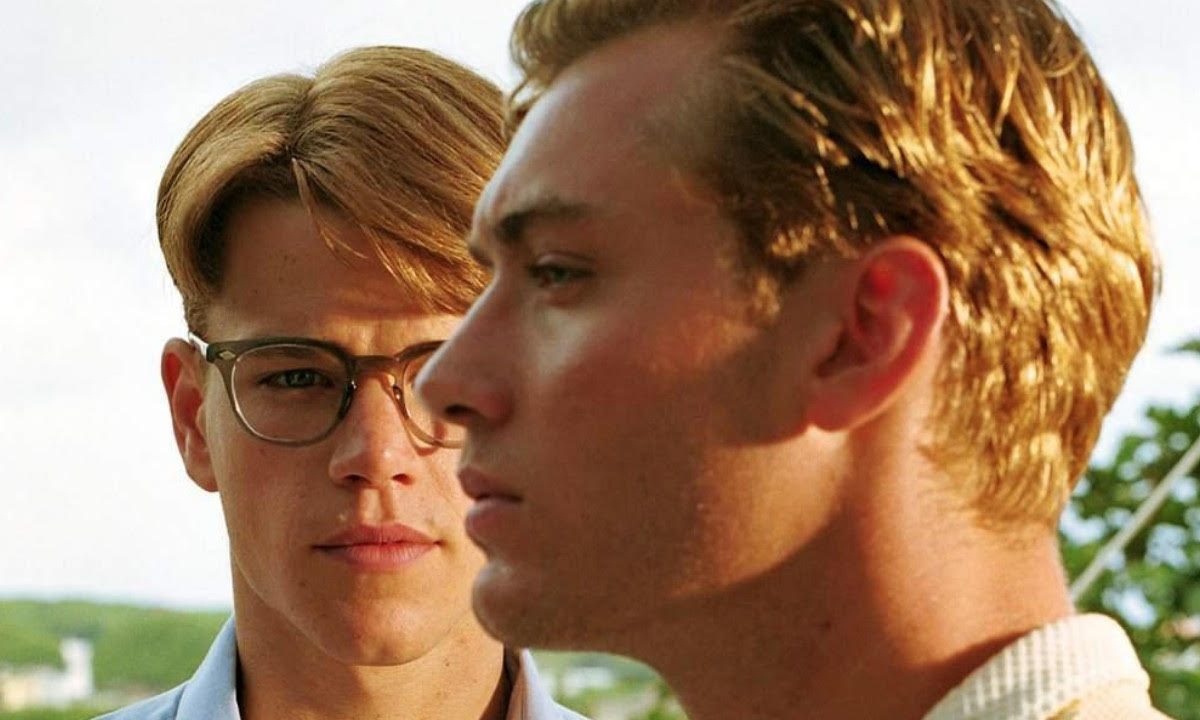

The second adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley, made under its own title in 1999 by writer-director Anthony Minghella, has become the dominant pop-culture image of Ripley, and Matt Damon’s take on the character exhibits more insecurity and self-loathing than Delon’s. Damon’s eager Ripley is desperate for the attention of the handsome, arrogant Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law), whose approval initially seems unattainable.

Both Ripleys are hired by Philippe/Dickie’s business-tycoon father to bring his wayward son home from Italy, where he’s been living a life of leisure with his girlfriend Marge (Marie Laforêt in 1960; Gwyneth Paltrow in 1999). Purple Noon opens with Tom and Philippe already spending time together in Italy, teaming up for a prank on a blind man and a later deception with a pretty woman they meet on the street. Minghella spends more time examining Ripley’s motivations, showing his life of poverty and artifice in New York City, the way he yearns for the glamour that the Greenleafs can provide.

In Purple Noon, when Ripley puts on Philippe’s clothes and playacts as the confident, sophisticated expat, kissing his own reflection in the mirror, it’s an act of narcissism, not sexual attraction. Minghella plays up the homoerotic tension between Ripley and Dickie, with Damon adding an extra undercurrent of self-doubt to his portrayal. In both cases, though, Ripley’s toxic jealousy ultimately leads to murder, as he resorts to increasing violence to maintain the position he’s established for himself within high society.

Purple Noon focuses more on logistics, with multiple bravura sequences of Ripley going to elaborate lengths to hide dead bodies and cover up his crimes. Minghella’s focus is more internal, as Ripley finds resources of deception and malice in himself that seemed previously hidden. Delon’s Ripley is the same debonair charmer at the beginning of the movie as he is at the end, after all the terrible acts he’s committed, but Damon’s Ripley seems like a new person — or perhaps his true self, finally allowed to run free.

It took much longer for Highsmith’s second Ripley novel, 1970’s Ripley Under Ground, to make it to the screen, and then only in a weak adaptation lacking the intrigue and complexity the character warrants. In director Roger Spottiswoode’s 2005 film, Barry Pepper plays a petulant, horny version of Ripley, with floppy hair and ill-fitting suits, who’s the mastermind of an art forgery scheme involving his late painter friend Philip Derwatt (Douglas Henshall).

When Derwatt kills himself on the eve of his biggest-ever opening, Ripley convinces Derwatt’s agent Jeff Constant (Alan Cumming), girlfriend Cynthia (Claire Forlani), and fellow artist Bernard Sayles (Ian Hart) to hide the body and pass Derwatt off as a living recluse, to continue bringing in money from his existing paintings as well as new forged works by Bernard. Although the scheme is largely the same as in Highsmith’s novel, it comes off as paltry and cheap in Spottiswoode’s hands, with the setting awkwardly moved to the present day.

Willem Dafoe is miscast as the earnest American art collector who starts to suspect the forgeries, and Australian actress Jacinda Barrett is even more grossly miscast as Ripley’s sultry French love interest Héloïse Plisson. Pepper struggles to express Ripley’s cold, sociopathic stare, and the movie’s aggressively heterosexual version of the character, complete with multiple uncomfortable sex scenes, seems like a misguided attempt to refute the fluid sexuality in Minghella’s film. Only Tom Wilkinson, as a British police detective who doesn’t buy any of Ripley’s bullshit, comes off well, because he could just as easily be calling out the movie’s own sloppiness.

Like The Talented Mr. Ripley, Highsmith’s third Ripley novel, 1974’s Ripley’s Game, has been adapted twice, with markedly divergent results. Neither film is entirely successful, but both offer the artistic ambition that’s completely absent in Ripley Under Ground. German filmmaker Wim Wenders landed the rights to the novel before it was even published, and his take on it in 1977’s The American Friend often plays like an abstraction of both the Ripley character and the thriller genre. The plot elements of Highsmith’s book are present, but they’re buried under layers of obtuse existential musings and deliberately distancing aesthetic choices.

As the second actor to play Ripley, Dennis Hopper could not be further from Alain Delon, playing the character as a Hopperian twitchy weirdo in a cowboy hat and cowboy boots. Wenders resurrects the artist Derwatt (played by filmmaker Nicholas Ray) as a forger who’s essentially copying himself, after faking his own death. Ripley is his fence, traveling from New York City to Europe to auction off new “rediscovered” Derwatt works. That’s where he meets unassuming picture framer Jonathan Zimmermann (Bruno Ganz), who makes a slightly rude comment at Ripley’s expense when they’re introduced.

It’s not easy to discern Ripley’s motives in Wenders’ elliptical presentation, but Italian filmmaker Liliana Cavani makes things clearer in her 2002 adaptation under the novel’s original title. Her Ripley (John Malkovich) is more in line with the Damon version, and he’s clearly insulted by his neighbor Jonathan Trevanny (Dougray Scott) at a dinner party. Hopper’s Ripley expresses uncharacteristic distaste for murder when he’s approached by gangster Raoul Minot (Gérard Blain) with a demand to carry out an underworld hit as payment for a debt. Malkovich’s Ripley instead sees the offer from his former associate Reeves (Ray Winstone) as an opportunity to play a sadistic trick on the unwitting Jonathan.

Both Jonathans are terminally ill, although in The American Friend, Minot deceives Jonathan into believing his condition is worse than it is. Wenders spends more time with Jonathan than he does with Ripley, who’s more of a sporadic, chaotic presence in Jonathan’s life as he’s pressured into carrying out contract killings for Minot. “You are too sensitive, Tom,” Minot says, an accusation that no one would make to any other version of Ripley. Hopper’s Ripley comes to Jonathan’s aid out of a sense of guilt and regret, while for Malkovich’s Ripley, it’s just a matter of staying in control of the game.

In Ripley’s Game, Ripley has blossomed into a confident, amoral serial killer, although he’s still insecure enough to let an overheard insult launch him into an intricate revenge plot. Malkovich gives Ripley a serpentine charisma, and when he ravishes his much younger Italian girlfriend Luisa Harari (Chiara Caselli), it feels like the result of his predatory attitude to all of life’s pleasures, rather than the clumsy overcompensating of Ripley Under Ground. Hopper’s Ripley barely registers as a real person, while Wenders devotes his time to Jonathan’s mental unraveling. Cavani, however, never loses track of her devious title character.

Like James Bond or Batman, Ripley is a character who can withstand many interpretations without losing his essence. He’s an embodiment of masculine pride, a man who gets away with anything because he never considers the idea that he won’t. Highsmith understood that allure in 1955, and filmmakers and actors continue to be fascinated by its seductive power. Ripley draws in artists and audiences just as effortlessly as he draws in his victims.